- Books & Workbooks

- Free Courses

- Free Membership

- The Nomadic Scholar

- Persuasion Mastery

- Behavioural Mastery

- Testemonials

- Free Connection Call

- 15th March 2020

- 45 minute(s) read

How To Become A Genius- The Polgár Experiment

In this article I write about the unbelievable story of the Polgár’s. The family who successfully created three geniuses on purpose.

A girl walks into a bar…

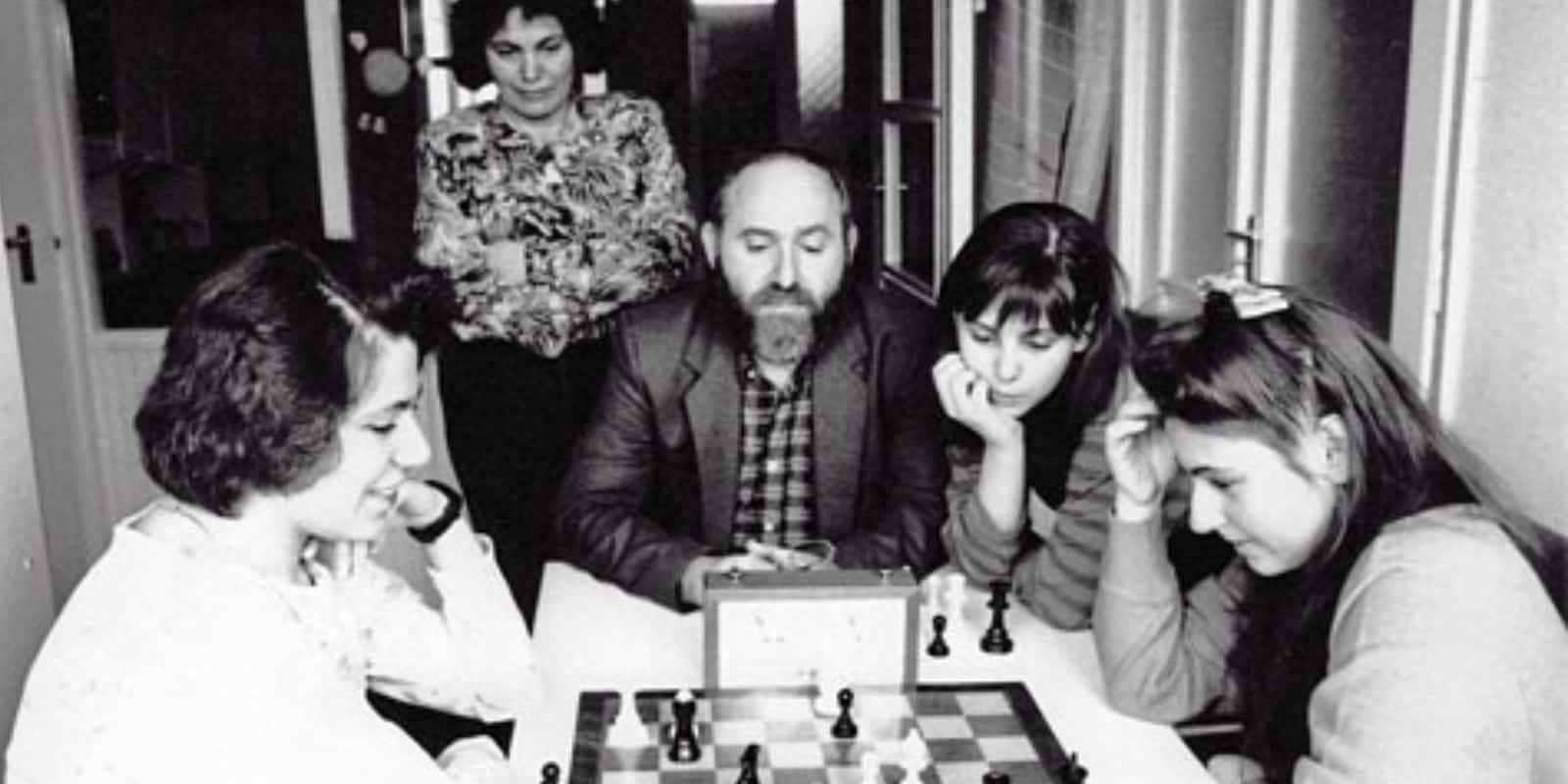

In the summer of 1973, a father and his daughter walked into a chess club in Budapest. 1

The club was full of heavy cigarette smoke and elderly men who came there day after day to play chess.

The father approached the gentlemen.

The old men could not believe their ears when they heard László Polgár challenge them to play against his four-year-old daughter, Susan Polgár.

László put a pillow that he brought from home on one of the chairs so his daughter could reach the table.

The old chess foxes could not believe their eyes when little Susan won one match after another.

Who the hell was this kid?

The First Female Chess Grandmaster

Thirty years later Susan Polgár, the world’s first female chess grandmaster was ready to give her usual Thursday night lecture at the New York Chess club when she announced to the room, “I have a special treat for you tonight!“. 2

“Tonight, everyone will get to play me“ Susan, 36 said with a gentle, but confident smile on her face to all the other chess players in the room.

The atmosphere in the room tensed, everybody transformed from student to competitor.

Everyone except Susan.

They were playing blitz chess, a form of chess where they not only played against one of the best chess players of all time in Susan Polgár but also against the clock.

First in line, was a young Serbian who tried to play aggressively, Susan managed to beat him in no time.

The young man stood up, shook his head in confusion, and made room for the next one.

It took Susan minutes to defeat her next two opponents, the last one to beat was a reluctant and shy teenage chess student.

While defeating him, she mentored him by saying, “Once you have a winning position, play with your hands, not your head. Trust your intuition“.

When Susan was the age of the boy, she already dominated the adult chess world and crushed competitor after competitor. 2

When she was 16 years old, Susan participated in the New York Open Chess competition, a prestigious tournament for the best of the best.

Although Susan was dominating her competition, as usual, there were two other participants in the tournament who caused quite the fuzz: Susan’s 11-year-old sister Sophia, and her 9-year-old sister Judit.

In particular, little Judit left the crowd in awe, when the 9-year old battled five players at the same time while being blindfolded.

The success of the Polgár’s did not go unnoticed, and Susan appeared on the cover of the New York Times shortly after the tournament.

By the time she was 21, Susan had become the first woman ever to earn the title of Grandmaster from the World Chess Federation.

In 2002, her sister Judit Polgár’, who by then was ranked as the eighth-best players in the world, would win against the reigning champion and living chess legend Gary Kasparov.

The same chess master who said earlier:

Women, by their nature, are not exceptional chess players: they are not great fighters.“ Gary Kasparov

But did he have a point? After all, only 11 out of the world’s 950 grandmasters are female. 3

Are the Polgár’s sisters born prodigies, who by a twist of genetic fate, were blessed with more talent than others?

This assumption could not be further from the truth…

Letters To Klara

47 years before Judit beat Gary Kasparov, László Polgár, a Hungarian psychologist and father of the three chess prodigies wrote a series of letters to a Ukrainian foreign language teacher named Klara.

The letters were not filled with Shakespearean declarations of eternal love; instead, they revolved around a precise and unprecedented pedagogical experiment that László wanted to conduct with his unborn children.

After studying the lives and achievements of over four hundred of the greatest intellectuals of our time, László believed he had identified the secret ingredient to high achievement: early and intensive specialisation in a particular subject. 4

A genius is not born but is educated and trained….When a child is born healthy, it is a potential genius”. -László Polgár

László rejected the idea of innate talent, and he believed that the public school system could only be successful in producing mediocre minds.

He had the idea that with hard work and the right kind of environment, everybody could become a genius.

László’s plan of proving the world wrong impressed Klara, and she got on board with the experiment of grooming three geniuses, and shortly after they got married and Klara got pregnant.

The Polgár’s decided that chess would be the perfect activity for their experiment; after all, only 1% of the top chess players in the world were women at that time.

In 1974, Klara gave birth to Sophie, 21 months later, Judit was born.

Soon after being born, the sibling’s curiosity was sparked by seeing their father teaching chess to Susan, the oldest of the three sisters.

They became interested in chess as a consequence, and with that, Polgár had not only one but three “subjects“.

So, how good did the three sisters do in chess?

Well, not bad, I would say.

After being recognised as the top-ranked female chess player in the world, Susan Polgár was the first woman in history to win the Chess Triple Crown, and the first one to qualify for the Men’s World Championship in 1986.

The second daughter, Sofia Polgár, went on to become a top ten female chess player in the world, and she also beat several other male grandmasters during her career.

Finally came Judit Polgár, born in 1976, she achieved the highest chess results among the three legendary sisters.

Judit is nowadays widely recognised as the strongest female chess player of all time.

She was also the one who broke Bobby Fischer’s record when she became at the age of 15, the youngest grandmaster of all time.

The childhood of the Polgár sisters was extraordinary, and it challenges the idea that nature trumps over nurture.

Are Geniuses Born Or Are They Made?

László’s crazy and maybe unethical experiment was successful in his attempt to “produce“ miracle children.

I would even go so far as to say that the Polgár family refuted the idea that geniuses are the mere consequence of biological flukes.

In that regard, László’s Polgár proved his theory that he made over 50 years ago, which states: genius-level performers are not born, they are made.

In case nobody ever told you this: there is a genius sleeping in your heart who waits to be awakened.

But it is not going to wake up by itself.

But what can you do to become everything you can be?

Before we discuss the psychological makeup of a genius, let us first identify what a genius is…

What Is A Genius?

If I am not for me – who is then for me; but if I am only for me – why do I live?” – The Talmud “The only geniuses produced by the chaos of society are those who do something about it. Chaos breeds geniuses. It offers a man something to be a genius about”.- B.F. Skinner “Genius is the recovery of childhood at will”. – Arthur Rimbaud

While we, up to this day, have not agreed on a scientifically precise definition of a genius, we all know intuitively what a genius is. 5

Or so do we believe.

The first thing that comes to mind when we think of the word genius is a super nerd, a la Stephan Hawking or Albert Einstein, a person who is born with superior or intellectual talent, who was predestined to achieve what normal people could never achieve.

Many psychologists believed that the intellectual superiority of outstanding people has its origins in the anatomy of their brain.

After Einstein’s death, for example, a team of psychologists analysed his grey organ anatomically (weight, volume, and folding of the brain), but they did not find anything that was not normal. 6

So, if it is not the brain itself, what is it?

Since László Polgár dedicated his life to the idea that geniuses can be produced, let us listen to his parameters:

Genius = Work + Luck + Favourable Circumstances Every healthy child may be led to the summit. The fact that the majority of children can learn a new language between the ages of 1 – 2 proves this. Think about it, is this not an achievement of genius? If they continue, at the age of 10, they can speak 5-6 languages. This genius results firstly from education and self-education. The opinion of world-famous geniuses also confirms this assertion. Let me cite some examples: T.A. Edison: “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration”. Ch. Chaplin: “Talent is nothing; discipline is everything”. Cuvier: “Genius is firstly attention”. Gorkiy: “Talent is the love of work”. J.S. Bach: “Anyone can achieve my level if he is a diligent as I have been my entire life”. J.W. Goethe: “Genius? Probably merely diligence”.

de Balzac: “Every human talent consists of two parts: patience and time”.

According to László Polgár, being genius is not an inborn trait; it is a level everybody can achieve in theory.

Yes, also you.

He identified three different levels that a person has to overcome:

A fully realised genius is the same, in my opinion, as an outstanding person. An outstanding person differs on the one hand quantitatively from the average (they know much more than the average person), and on the other hand, they realize in society a more valuable, more original creativity. Being outstanding comes in different stages. I distinguish three: Candidates or pre-geniuses (1-5% of every domain) Geniuses (0.2 -0.5 % of every domain) Super-genius (1 in every domain) Thus follows: The handicapped Idiots: very retarded mentally Imbeciles: moderately mentally retarded Feeble-minded: a little mentally retarded The normal Adequate people: minor capability Average people: natural Capable people: more capability The outstanding (geniuses) Unusually capable: candidate or pre-geniuses Super-capable: geniuses Extraordinarily capable: super-geniuses Of course, these divisions are only relative. Obviously, every concrete person can move from one category to another.

What does this mean?

This means that once you have identified an area of your life that you want to master, there are different milestones that you can achieve to work yourself up to the level of a genius.

Read that sentence again.

In the case of the Polgár’s, their parameters were, of course, chess related.

For chess, these success steps are precise and measurable; one of the reasons why Polgár choose this particular domain.

There is a system that is called “Elo Points“, and it measures how good a chess player is. 7

- – Super-geniuses (above 2650 Elo Points)

- – Geniuses (2550-2650 Elo Points)

- – Candidate geniuses (2450-2550 Elo Points)

All three Polgár sisters had stretches where they were playing at a super-genius level.

This indicates that every domain has levels that we can climb, this means that no genius is just born, they climb the ladder, and they can fall off the ladder of success if they stop practising their craft.

The purpose of this article is for you to learn about Polgár’s blueprint and apply it to your personal domain of interest so that you can become a genius in your field.

In the following part of this article, we are going to deconstruct what characteristics you can emulate from the Polgár’s to maximise your potential,

The five-ingredients of a genius that you are going to find in the next part of this article, are derived from my observation of the beautiful story about this wonderful family, of course, they do not represent their ideas but mine.

Ingredient One – Rage To Master

Many things can be acquired with money, many by deceit, and many by falsehood. But there is one thing that can be obtained only by honest labour, for which a king must work as hard as a coalman… and that is knowledge”. – The Talmud “A true scientist lives a monastic life, separate from the affairs of the world, dedicating himself completely to his work. ” – László Polgár “Instruction without discipline is like a windmill without water ” – Comenius

While I mainly focused on the positive parts of Polgár’s experiment in this article, it is impossible to read about the three miracle sisters without acknowledging the amount of hard work they invested into the development of their craft.

The Polgár’s possessed something that Ellen Winner, a psychologist from Boston College, calls the “rage to master”.

A trait that can be defined as an unstoppable motivation to excel in a domain of interest. 8

I had an inner drive; I think that is the difference between the very good and the best”. Susan Polgár

Was this rage to master something the Polgár’s were born with or was it something that was developed?

I believe it was the latter.

One way I can see the three children develop the rage to master, was when László Polgár put his children in a 24 Chess Marathon in Dresden:

In 1985 only Zsuzsa and in 1986 also her two younger sisters played in the tournament, Zsuzsa was 15, Zsofi was 9 and a half, and Judit 8). According to the rules, they had to play 100 matches in 24 hours, so they had to keep attentive with great effort, practically without rest. (There were only three short 20-minute pauses for food). Added to this, they had to sit at the chess table after a 16-hour train journey. László Polgár

With challenges like this, it is no wonder that the children developed an extraordinary persistence.

It again shows that great people are not born; they are forged.

Every successful person has been a fanatic at some point in their lives; the Polgár’s are no exception.

Nothing was given to them; everything was earned.

If the chest pieces of the three sisters could talk, they would tell you about the endless hours of practice, the many moments where they did not feel like showing up but still did.

The pawns would sing about defeat, about sweat, about tears, about obsession, and about the heavy burden of being born to a father who has crushing expectations.

It is also impossible to overlook the insane work ethic of the father, László Polgár himself:

As concerns my view of life: I have worked 15 hours a day since I was 14. For me, quality is the main thing. I wish to do everything always at the highest level. Mediocrity, the orientation to the middle, I refuse out of principle. I strive for the summit despite obstacles, obeying the admonition of Michel de Montaigne: “In a great storm, sailors in ancient times invoked Neptune: O God! You will save or destroy me according to your will. But whatever you will, I will steer my ship as necessary!”

Human beings are imitators; we learn through observation.

The opinion of Albert Banduras, one of the most famous behaviourists of all time, also confirms this assertion:

Fortunately, most human behaviour is learned observationally through modelling from others”. – Albert Banduras.

In the video below, you will find The Bobo Doll, an experiment that shows that the quality of our behaviour often comes down to the quality of people we are surrounded by. 9

Ingredient Two – Deliberate Practice

The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones”. Confucius “Do not let the sun set without doing something”. Latin Proverb “We must believe that we are talented in some area and we must absolutely attain it”. M. Curie

In 1985, Benjamin Bloom, a professor of education at the University of Chicago, investigated the critical factors that contributed to talent. 10

In his book, “ Developing Talent in Young People” , he takes a deep look at the upbringing of 120 elite performers who had won international competitions.

Bloom found that there were absolutely no early indicators that could have predicted genius-level success, not even IQ.

What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn if provided with appropriate prior and current conditions of learning.“ Benjamin Bloom

The only difference Bloom found was that extraordinary performers had practised intensively, studied with dedicated teachers, and had been supported enthusiastically through their developing years.

Anders Ericsson, a professor of psychology at Florida State University, argues that “extended deliberate practice” is the true key to success.

Ericsson interviewed 78 German pianists and violinists and discovered that by the age of 20, the most successful artists had spent approximately 10,000 hours on polishing their craft, on average 5,000 more than a less accomplished group. 11

Even the most motivated and intelligent student will advance more quickly under the tutelage of someone who knows the best order in which to learn things, who understand and can demonstrate the proper way to perform various skills, who can provide useful feedback, and who can devise practice activities designed to overcome particular weaknesses.” ― Anders Ericsson, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise

All three of the Polgár’s had amassed over 10,000 hours of deliberate practice by the age of 12. 12

Deliberate practice does not mean to simply live in a cave and study blindly; watching every episode of Emergency Room will not make you a doctor.

When most people practise, they focus on the things they already know how to do; deliberate practice is different.

What all three Polgár’s had in common was that they were not only working hard but also smart.

After every loss, they deconstructed the match and investigated what they did wrong so they could weed out their weaknesses and become better incrementally.

While starting at an early age can definitively be an advantage, I find it unbelievably refreshing to learn that with hard work and the right strategy, we can actually climb the mountain of success.

Leo Tolstoy (1847–1910), once observed that the people who asked him if they had what it takes to write a book, never actually tried to write one.

Mainstream media is full of overnight success stories, but when we take a closer look at the admired “naturals“, we always find that they have spent an incredible amount of time and energy into the strategical improvement of their craft.

While this iceberg of work might feel intimidating, it is important to notice that the ladder of success is climbable and that it will not take forever to get to the top.

10,000 hours is not forever, so if you do not have anything better to do, why not start TODAY at mastering your craft.

Ingredient Three – Choice Architecture

A person who shapes his environment shapes his destiny, his society and himself. ” László Polgár “Other people are among the most elementary needs of the person. ” K. Marx “Through others, we become ourselves”. Lev S. Vygotsky

The second and most obvious reason for the Polgár’s extraordinary development was that they grew up in a chess factory.

Thousands of chess books were stuffed into the shelves, trophies and posters hung everywhere.

Entire walls were cluttered with records of previous games for unlimited analytical pleasure.

Paintings that depicted 19th-century chess scenes could be found in many rooms.

The Polgár’s home was like a carefully designed and permanent chess boot camp:

The motivation for succeeding in chess was just there in the atmosphere of our house” Susan Polgár

While motivation plays a big role in mastering any field, the environment we are surrounded by seems to affect us even more.

While writing a chapter about the impact of our environment for my upcoming book, “ The Behaviour Architect” (coming soon), I interviewed Dr Anne Thorndike, a medical professor at Harvard University for The Psychology Podcast with Daniel Karim.

Dr Thorndike and her colleagues believe that it is possible to improve the eating habits of thousands of hospital employees and visitors without the slightest bit of motivational manipulation. 13

Dr Thorndike and her colleagues designed a six-month study where they altered the “choice architecture” of the hospital cafeteria.

They started by relocating the drinks in the room. Before the study, the refrigerators stood next to the cash registers, and they were filled with soda only.

The research team now added water as an option to each refrigerator, and additionally placed a basket of bottled water next to each food station across the room.

While the unhealthy soda was still in the refrigerators, now the staff and visitors had the choice of taking water instead.

The image above shows you how Dr Thorndike and her colleagues manipulated the environment to get people to make healthier choices without even talking to them. To the left, you see the room before the changes (Figure A), and to the right, you see the room after the changes (Figure A). The dark boxes indicate where water was available.

What did they find?

Over the next three months, water sales increased by 25.8%, while soda sales dropped by 11.4%.

What we can learn from Dr Thorndike’s work and from the choice architecture of László Polgár, is that where we are, determines what we do.

B.F Skinner knew this almost 80 years ago when he said:

The ideal of behaviourism is to eliminate coercion: to apply controls by changing the environment in such a way as to reinforce the kind of behaviour that benefits everyone.“

A threatening realisation isn’t it?

After all, we all have been brought up with the idea of the American dream that states that the world is a fair and just place, and everybody can achieve their dream.

But in reality, our environment either makes or breaks us.

In 2018, my family had to learn that this principle cuts both ways.

At the end of that year, my father, a cigar connoisseur, bought himself a beautiful humidor.

Due to his love of cigars, my father believed it would be a good idea to invest a ton of money in giving his little babies a better home.

He placed the humidor on his English desk, where now, always in reach, he had an endless supply of perfectly freshly moistened cigars.

Pre-purchase, it was one of his rituals, to once a day, to leave his work behind and go to the cigar store to chat with his trusted cigar dealer about life and enjoy his break with a little puff.

After my father purchased the humidor, all he had to do was to spin his English chair around to grab a cigar whenever he felt like it.

One month after the purchase, my father was smoking four cigars a day.

Two months after the purchase, my father had a heart attack and found himself in the hospital.

Luckily, he survived.

Consciously, my father did not choose to smoke more, he knew very well that one cigar a day was risky enough, but because he chose to reshape his environment, unknowingly, he created an environment for himself which promoted smoking to the degree that nearly ended him.

What I am trying to say by this story: the results you currently produce are indicators for the quality of your environment.

Ask yourself right now:

To what kind of judgment would a stranger come to if they would observe your living environment?

If they would take a look at your room, what would they assume about you?

If they would take a look at your friends to predict your future, what kind of future would they prophesize for you?

Just like the Polgár’s transformed their home into a chess shrine, you need to align your living environment with your goals.

Here are a few ways you could redesign your environment:

- If you want to stop yourself from cheating on your diet, establish a no sweets policy at your home.

- If you want to get in shape, put your running shoes in front of your bed.

- If you want to drink more water, put two big full water bottles next to your bed.

- If you want to stop yourself from procrastinating, sell your TV.

- If you want to improve your speaking skills, join a debate team.

- If you want to get rid of your depression, get a dog.

- If you live with somebody who lives a pathological life, move out of the apartment.

Ingredient Four – Specialisation

Human history is a contest between catastrophe and education”. – H. G. Wells “Chance can create not only a thief but sometimes a great person”. – G.C. Lichtenberg “A man who lives everywhere lives nowhere”. Marcus Valerius Martial

During his time as a student, László Polgár was obsessed with studying the biographies of approximately 400 great intellectuals from Socrates to Einstein.

While reading those biographies, he had identified a common theme — intensive specialisation in a particular subject.

Polgár started to put this discovery into practice, and started to educate his three daughters before they were three years old; when they turned six, he started to ” specialise” them. 12

Polgár decided to home school his children because he did not believe that our generalised school system could be successful in anything else but to produce mediocrity.

The first characteristic of genius education – I could say the most important novelty distinguishing it from contemporary instruction – and its necessary precondition, is early specialization directed at one concrete field.“ – László Polgár

So, to become a genius in something, the first step is to decide what one wants to be a genius in.

I am sure you have noticed, but this is the exact opposite idea of the generalised school system that we have in most countries of the world.

For that very reason, Polgár made the early decision to home school his children:

It is generally known that you are a pedagogy fanatic; however, you did not put your daughters in school; they did their studies as private students. Why? The fact that I did not send my daughters to school is, of course, connected to the fact that I hold an unfavourable opinion of it. I criticize contemporary schools because they do not educate for life, they equalize everyone to a very low level, and in addition, they do not tolerate the talented and those who diverge from the average. Let us take this step by step, and start with your first remark: schools do not educate for life. Is the old Latin saying “One learns not for the sake of school, but of life” pointless? Contemporary schools are separate from real life in that they function sort of as laboratories. There is no link with domestic or political or local public life or the everyday cares of living one’s life on the one hand, and school on the other. My daughters, who have never visited a school, grew up much more in the context of real life. Contemporary schools do not promote a love of learning. They do not inspire to great achievements; they raise neither autonomous people nor communally-oriented ones. Schools do not manifest or develop potential capabilities in people, at least as much as they could. It seems to me that the second point of your critique of schools is related to this. That is, they equalize everyone to a very low level. How would you clarify this? It’s a simple matter. If all the schools in the country are of only one type, the model is like this: in each school, there are, besides a few outstanding people, many mediocre and weak people. The mediocre are closer to the weak than to the outstanding. Of course, a teacher cannot adapt to those few outstanding people, so the teacher presents material that is appropriate for the majority. Thus, for the outstanding, class time becomes tedious. Even if the teacher wished to, the teacher cannot “tailor” the study material for most of the students’ individual needs. So, they cannot make each child work to their potential. Too often they must make the whole class mechanically repeat more or less identical tasks. In the current organization structure, they only speak about instruction providing problem-solving skills, but in practice, this is unrealizable. Thus, both pedagogues and students suffer in school.“ László Polgár 13

And, Polgár was not the only expert who believed that our current school system is not only ineffective but harmful. Here are a few famous people who failed at school, or in better words; were failed by the school system.

Billionaire and founder of the Virgin brand, Richard Branson, struggled in school with various learning difficulties but has since taken the world by storm.

Branson had enough of school and dropped out of it at the age of 16 in order create a magazine. Today, he is the owner of more than 400 companies. 14

I think by the age of 16, for most they should have learnt all the basics that they need to get out into the outside world, ideally, they should go off and travel for a year, and if they want to go to university they should be able to go to a university course that is not longer than about two years.” – Sir Richard Branson

Thomas Mann failed three times during his school studies; he later became one of the most famous writers of his generation.

Another one who might surprise you: Albert Einstein.

Einstein was known as a notoriously bad student, and one of his teachers once noted, “He [Einstein] thinks slowly, is agitated, obsessed with stupid dreams”. 15

The only thing that interferes with my learning is my education”. Albert Einstein

The great Charles Darwin often got in trouble for being lazy and day-dreaming.

Darwin himself stated, “I was considered by all my masters and my father, a very ordinary boy, rather below the common standard of intellect”.

Darwin eventually became a huge figure in the field of Biology.

While I am light years away from the achievements of the gentlemen above, and maybe thank god for that, I know what it feels like to fail at school.

In Germany, when you hit the fourth grade, the teachers evaluate your potential and your capabilities and put you in a “fitting school category“.

There were three categories when I grew up:

- Gymnasium (For talented teens)

- Realschule (For mediocre teens)

- Hauptschule (For idiots)

I still remember how stupid I felt when I got the “Hauptschule Diagnosis“, not because I was labelled as untalented by my school authorities, not because I was separated from my friends or because I had to go home and tell my mom that I did not make it, I felt stupid because up to that point I thought I was a smart kid.

In Germany, graduating from gymnasium is a precondition to studying at any university, so with that diagnosis, my dreams of becoming a psychologist were crushed.

Stuck with incompetent pedagogues who hated their job, and surrounded by other angry and impoverished children, I began to resent school.

The campus became my prison, and I was looking for every possible chance to escape it.

I became an even worse student, and I had to repeat the eighth grade two times before they finally had it with me and kicked me out.

When I was seventeen years old, I had no high school diploma, and I was not allowed to attend any normal school in Germany because it is only allowed to repeat the same class twice.

Just as László conducted an experiment to turn his children into geniuses, my environment succeeded in turning me into a failure of epic proportions.

Academic Failure = Lack of Deliberate Practice, Dysfunctional Environment + Generalised School System + Subpar Educators + No fun + No Orientation Towards the Future + Bad Habits

After years of blaming the living daylights out of myself, I began to understand that human beings are systematic creatures and that it was not only me who needed repair.

Bad apples usually grow on sick trees…

But what does a good system look like?

What would a day in the genius producing home-schooling system of László Polgár look like?

In his book “Raise A Genius“, he states:

4 hours of specialist study (for us, chess)

1 hour of a foreign language. Esperanto in the first year, English in the second, and another chosen at will in the third. At the stage of beginning, that is, intensive language instruction, it is necessary to increase the study hours to 3 – in place of the specialist study – for 3 months. In summer, study trips to other countries.

1 hour of general study (native language, natural science and social studies)

1 hour of computing

1 hour of moral, psychological, and pedagogical studies (humour lessons as well, with 20 minutes every hour for joke-telling)

1 hour of gymnastics, freely chosen, which can be accomplished individually or outside of school. The division of study hours can, of course, be treated elastically. 16

If you take only one thing away from this article, let it be this: You can only be a world champion at one thing.

To win a game, you first need to decide what kind of game you want to play.

How many people do you know who graduated high school or even college, and have absolutely no idea what they are going to do with their life?

Should it not be the purpose of school to send us equipped with a sharp mind into the world to achieve our dreams?

For most of us, when we leave college, we are not only unprepared but crippled by the debt we had to drown ourselves in to attend university in the first place.

Jack Ma, Founder of the Alibaba group, once told his son:

You don’t need to be in the top three in your class, being in the middle is fine, so long as your grades aren’t too bad. Only this kind of person has enough free time to learn other skills“.

I can confirm this statement. When I got kicked out of high school, while at first, I felt like my educational journey was over, I found that I was indeed liberated.

I did not have to take a single course that did not interest me, neither did I have to listen to the teachers who told me I will never amount to anything, and I also did not have to be scared of getting beaten by other kids in my schoolyard.

I was free.

I began to study on my own, and my new teachers were Sigmund Freud, Leo Tolstoy, Viktor Frankl, Friedrich Nietzsche, B.F Skinner, and Carl Rogers, and I never heard a single word of discouragement from them.

Out of that journey of individuation, ensued a form of radical freedom that allowed me to study the only thing that ever interested me: the human condition.

I was specialised by accident.

The good thing about being labelled as a failure is that nobody expects anything out of you anymore, I was finally allowed to become myself.

Five continents and hundreds of devoured books later, I manage to find my way into your life, and I would like to thank you for your precious attention and ask you something:

Are you currently pursuing what is expected, or are you living an authentic and meaningful life?

When I stumbled over the story of the Polgár’s, I was reassured that my path had turned out to be the correct one, but I was also worried… how many people are doomed for mediocrity because nobody told them that choosing a single field of mastery is not optional but a necessity?

If you have not already chosen a path that will lead you towards the ultimate goal, which is fully actualising your potential, I challenge to do this right now:

If you were to be sent to Polgár’s genius school TODAY, what kind of speciality would you choose to practice for six hours a day?

In my interview with world-renowned behaviourist Dr Susan Weinschenk, I learned that people align their behaviour with their perception of who they think they are.

This means that your current results are a reflection of your current identity.

The most powerful asset that the three Polgár sisters were equipped with was a high-quality identity: a Future Chess Champion.

Every identity, whether it is external or self-imposed, comes along with a set of habits, values, and belief systems.

When I was labelled a failure, I subconsciously acted according to that role.

I did not take care of my health because clearly, I was not a valuable thing… I got into fights to experience some sense of power… I developed all sorts of addictions because why bother preserving myself for a future that is going to be depressing anyway?

László Polgár gave his children a high-quality identity right away, and with that, they had a blueprint of what they had to do and who they have to become to reach a future that is worth suffering for.

Here are a few things you can do to align your identity with your goals:

- Investigate the identities of your heroes and adopt their habits, clothing, values, and belief systems (Of course, only emulate virtues that are relevant for your dream).

- Order posters of your heroes and put them on your wall.

- If you want to get better at your career, transform your bedroom into a library with books on your passion topic.

- Do not dress like the person you were yesterday, but like the person, you want to become tomorrow.

- If you want to lose weight, adopt the identity of an athlete.

- If you want to have more intimacy and connection in your life, identify yourself as a “people’s person“.

- If you want to become a better writer, start by calling yourself an author and write every single day.

- If you want to be more respected at your work, identify as a true professional and make it a self-imposed policy never to be late again.

- If you want to become a better basketball player, start by calling yourself a gym rat and truly dedicate yourself to the betterment of your game.

- If you want to become a better student, pride yourself on having a growth mindset and talk to your educators after every class about your flaws.

Your current results are a symptom of the current identities that you adopted, or that were forced upon you.

If you want to change, change the story about yourself first.

A high-quality identity, like the one from the Polgár’s (future chess champion), is a promise from the pedagogue to the student that states: If you follow the code of conduct that I am proposing, things are going to get better for you.

This orientation towards a meaningful future justifies that the pain of being is a basic spiritual need.

Viktor Frankl, the famous therapist and Holocaust survivor, confirms this theory:

Why are you not ending your life?“

This was a question Frankl often asked his depressed patients right away.

He did so, of course, not because he wanted to promote suicidal thoughts, but because he wanted to find out what exactly it was, that makes life worth living for the patient.

Some patients answered that they had unfinished career goals.

Others said they have someone that they want to be there for.

Frankl would then attempt to reconnect his patients with their life’s purpose so that they could again look into the future and carry their burden properly.

In his time in the concentration camps, the psychiatrist understood that an orientation towards a meaningful future is, indeed, the most powerful motivational force there is. 17

[Speaking of his experience in a concentration camp:] As we said before, any attempt to restore a man’s inner strength in the camp had first to succeed in showing him some future goal…Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on. He was soon lost. – Viktor Frankl

Have you ever been witness to a situation where an educator was asked, “Will this be on the test?“

Questions like this are indicators that the student is experiencing a lack of meaning, or in other words, they do not see how this educational investment is going to pay out for them in the future.

In our school system, we blame the student for such questions; we call them lazy and blame them for their disinterest.

In some cases, we even blame the biology of the student.

My good friend, Jeffrey, a young and brilliant creator, was once falsely diagnosed by his teachers with ADHD because he just could not stay attentive during his classes.

In his case, the educators did not only not take responsibility for the fact that Jeffrey and his other classmates could not make it through a single lecture without falling asleep, but they went so far as to blame his anatomy for it.

His class teacher, in collaboration with one doctor, ultimately forced him to take four different drugs just to stay attentive.

In the lecture below, Dr Jordan Peterson gives a variety of reasons why ADHD is over-diagnosed, and why prescribing ADHD medication does more harm than it does good.

In Jeffrey’s case, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattentiveness, and impulsivity were not symptoms of a brain disorder, but signs that his educators were unsuccessful in stimulating the young man’s talented intellect to the necessary degree.

He was also an extremely athletically gifted guy, who by nature had an awful lot of energy, but as his school physical education was only happening once a week, sitting quietly for nine hours a day was unnatural to him.

And if I am honest, I do not think that this kind of paralysing indoctrination is natural to anybody.

Research has shown, for example, that prescribing physical activity can be just as curative as prescribing pharmaceutical drugs. 18

I furthermore believe that this kind of denunciation of the student is originated by the lack of psychological understanding of emotional mechanics.

I asked myself recently:

Why was I so disinterested in my teachers while the Polgár’s soaked in every bit of information they could get?

The figure above, by Dr Jordan Peterson, is a good visualisation of the fact that human beings are goal orientated creatures.

Think of the Polgár’s, they all bought into the idea that becoming a chess champion was an attractive future destination.

When their father educated them, they knew that every hour of practice would move them closer to the place that they wanted to be.

Let us take a look at my own shortcomings…

When I had geography in the fourth grade, I asked my teacher why I had to study that subject; he told me: because you have to.

Not that geography is not important, but for me, it was not.

I even told my teacher that under no conditions will I ever work in the field, but still, he insisted that I had to study what everybody else studied, for years that is.

To be motivated as a child, one has to be convinced that the time and energy investment is worthwhile and will move one to a better place.

A professor once told me a bad joke that captures this principle…

Why did the chicken cross the road? Obviously, because the other side was better.

If you want to pause for a second and hold your belly from all that laughter, you can do that now.

The combination of daily failure and being imprisoned in a classroom that desperately tried to get me to a place that I did not find meaningful, caused me to avoid education entirely.

We can learn two things from this comparison:

- What is punished is avoided.

- What is rewarded is repeated.

If a student only experiences negative emotions in school, they either become a soulless puppet, or they will rebel against their spiritual tyranny and do everything they can to escape that prison.

The following experiment by John B. Watson, shows perfectly (and unethically) how we can learn to be afraid of neutral stimuli:

Why am I telling you all this?

The purpose of this chapter is to show you the importance of choosing a high-quality identity for yourself.

Only by architecting your ideal future identity can you evaluate your current life’s journey. If you never invest the time and energy to define your aim, you have absolutely zero chance of hitting it.

But how do you find out what kind of identity you should try to adopt?

Carl Jung believes that the things that put us into flow state are nature’s indicators to guide us toward maximum development. 19

The questions below are derived from my understanding of Jungian psychoanalysis. They are not direct quotes from him, obviously.

If you are not everything you can be, you will find the questions below helpful:

What makes you lose track of time?

What do you dislike in others?

What’s your definition of a “good” person?

What’s your definition of a “bad” person?

What did you want to become when you were a child?

If money would not exist, what would you do with your life?

If you would die next week, what would you regret?

What are the things in your life in need of repair?

Which experiences make you feel alive?

Which area of your life do you find the most meaning in?

Ingredient Five – Love

Neither a lofty degree of intelligence nor imagination nor both together go to the making of genius. Love, love, love that is the soul of genius”. ― Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart ”The teacher who is indeed wise does not bid you enter the house of his wisdom but rather leads you to the threshold of your mind”. — Khalil Gibran “Iron sharpens iron, and one man sharpens another”. — The Bible

The last, and in my eyes, the most important ingredient to forge a genius is love.

One thing that even the harshest critics of László Polgár’s radical pedagogical experiment cannot accuse him of is that he and his wife Klara did not care about their children.

László Polgár and his wife Klara literally had to fight for the education and realisation of their children. In one instance, Soviet authorities stormed the house of the Polgár’s with a machine pistol because the Polgár’s refused to send their children to the public school system.

If that kind of commitment does not secure you the dad of the year award, I do not know what would. 20

The Polgár’s believed that love was indeed a precondition to outstanding achievement, in his book Raise a Genius, he states:

Genius = Labour + Luck Happiness = Labour + Luck + Love + Freedom “Let us not fear to raise our children with optimism and courage (without begrudging the material expense!). Prodigies are not miracles, but natural phenomena; indeed, they must be formed as natural phenomena. Parents and society are responsible for the development of the children’s capabilities. A large number of geniuses are lost because they themselves never learn what they are capable of“.

Creating a genius is not a one-man job. It is a collective effort to realise an individual fully.

Before the Polgár’s started their experiment, they examined the childhoods of histories many most eminent people, and they noticed that behind every genius was a network of dedicated and caring educators:

We examined the childhoods of many eminent people and noticed that all who became geniuses specialized very early in some field, and we could also document that beside them always stood a father or mother, a tutor or trainer, who were “obsessed” – in the good sense of the word. So, on the basis of our research, we could rightly conclude that geniuses are not born one has to raise them. And if it was possible to raise an outstanding person, we definitely needed to try this. So, we did, and our attempt brought success.

The idea that behind every outstanding person stands one or many outstanding educators is hard to deny.

Let me give you a couple of case studies to prove this theory:

Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922)

Bell reinvented the field of communications by creating the first telephone, but years earlier, he struggled in school. Even though he was gifted at problem-solving, it is thought that he had trouble reading and writing, possibly as a result of dyslexia. He was eventually home-schooled by his mother. With her help, Bell learned to manage his challenges, and he went on to change the world. 21

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

According to many accounts, the world-famous artist may have had dyslexia.

Don’t think I didn’t try [to learn at school]”, he said. “I tried hard. I would start but immediately be lost”. – Pablo Picasso

Fortunately, his father, an art teacher, encouraged him to develop his artistic talents. His unique vision of the world came through in his powerful works of art. The rest is history. 23

Felix Mendelsohn (1809-1847)

The master musician would, in his short life span, came to be recognised as one of the most prominent composers of his time.

Felix’s mother, Leah Mendelsohn, a trained musician and artist, took care of his early musical education.

She made a continuous effort to developing Felix’s talent, and she regularly shipped in the world’s most eminent teachers to teach him.

Felix was, for example, from 1816 and 1817, tutored by Marie Bigot (a gifted and stimulating teacher who had been admired by both Haydn and Beethoven for her technique). 24

According to Radcliffe (2000), only on Sunday mornings was Felix allowed to wake up later than 5:00 am. 25

Thomas Edison(1847-1931)

Edison is today known as one of America’s greatest inventors and businessmen but was not always admired as a genius.

When Edison was in elementary school, he returned home one day with a letter from one of his teachers.

He said to her, ”Mom, my teacher gave this paper to me, only you are allowed to read it. What does it say?”.

Nancy Edison’s eyes teared up as she read the letter to herself.

“Your son is addled [mentally retarded]. We will not allow him to attend our institution any longer”,

After gathering herself, she faced Thomas and pretended to read the letter to him:

Your son is a genius. This school is too small for him and doesn’t have enough good teachers to train him. Please teach him yourself”.

Edison’s mother did not give up on her son and designed an excellent home-schooling routine for her Thomas, and Edison left his school behind without a second thought.

By the time his mother died, Thomas had become arguably the greatest inventor of the century. After her passing, Edison sifted through old family records and found an old brownish letter deeply hidden in his mother’s closet.

It was the letter from his elementary school that Edison’s mother received many years before.

Edison sobbed for hours, before writing with conviction in his diary:

Thomas Alva Edison was an addled child, that, thanks to the heroism of his mother, became the genius of the century.” 26

Moral Of This Story

You might ask yourself now: Well, I was not specialised in my early childhood, and a transcending educator did not groom me, so it is too late for me, isn’t it?

Not only is the answer to that question a clear no, but I would also argue that you have an advantage over all the eminent people that I wrote about in this long article.

I only need one word to tell you why: Technology .

The internet has caused a revolution that successfully democratised information.

If you were to travel back in time and tell somebody that future generations succeeded in developing a device that would you give you instant access to all pieces of knowledge ever collected, they would probably burn you at stake.

Technology, in that sense, is indistinguishable from magic.

While it is definitely advantageous to have parents who open doors for you, it is entirely possible to create your own success system around you.

In ancient times, only the most elite were given a chance to be tutored by experts. Today, you are just one email away from sending a mentee pitch to one of your idols.

Self-actualised people are communal treasures who not only achieve happiness by living an authentic and fulfilled life; they make things better for everybody around them.

I firmly believe that the fact that a person like me, labelled as an academic failure, now speaks to thousands of people through his blog about the power of learning is an indicator that the notion that everything is possible is indeed true.

I wrote this article to show you that there is clearly more to you than meets the eye and that there is a level out there where all your dreams and potential are realised.

It is indeed true, however, that geniuses are rare things, not because there is a lack of talent, but because we, as a society, only raise them occasionally.

Luckily for me, I had two stubborn parents who preserved my love for books and people, and who never stopped their unconditional belief in me.

I have learned over the years that education has the power to transform every wall into a door.

Therefore, I would like to pass on this family tradition and tell you something from the bottom of my heart:

I believe in your potential.

If you discipline yourself, align your environment with your goals, adopt a favourable identity, and surround yourself with people who want the best for the best part of you, you are going to be the champion you were always meant to be.

Thank you for reading,

- Flora, C (July 1, 2005) The Grandmaster Experiment [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/200507/the-grandmaster-experiment

- Myers, Linnet (February 18, 1993). “Trained To Be A Genius, Girl, 16, Wallops Chess Champ Spassky For $110,000” . Chicago Tribune.

- Howard, B. (2014, June 19) Explaining male predominance in chess [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://en.chessbase.com/post/explaining-male-predominance-in-chess

- Lundstrom, Harold (Dec 25, 1992). “FATHER OF 3 PRODIGIES SAYS CHESS GENIUS CAN BE TAUGHT” . Deseret News .

- Robinson, Andrew. “Can We Define Genius?” . Psychology Today . Sussex Publishers, LLC . Retrieved 25 February 2020 .

- Hughes, Virginia. (April 21, 2014) “The Tragic Story of How Einsteins Brain got stolen”. [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2014/04/21/the-tragic-story-of-how-einsteins-brain-was-stolen-and-wasnt-even-special/

- Elo, Arpad E (2008). “8.4 Logistic Probability as a Rating Basis”. The Rating of Chessplayers, Past&Present . Bronx NY 10453: ISHI Press International. ISBN 978-0-923891-27-5 . a Hungarian-American physics professor.

Kalb, C. (2018, May 1,). Exploring Characteristics of Prodigies. National geographic . Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/05/genius-child-prodigy-science-art-autism/

- Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961): Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63 , 575–582.

- Ericsson, K. A., Prietula, M. J., Cokely, E. T. (2007, July): The Making of an Expert. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2007/07/the-making-of-an-expert

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R., Th., Tesch-Romer, C., (1993): Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychological Review 1993, Vol. 100. No. 3, 363-406

- Dsouza, M. (201 9 ): “The Astonishing Success Story of the Genius Polgar Sisters“[Blog post]. Productiveclub . Retrieved from https://productiveclub.com/polgar-sisters-story/

- Anne N. Thorndike et al., “A 2-Phase Labeling and Choice Architecture Intervention to Improve Healthy Food and Beverage Choices,” American Journal of Public Health 102, no. 3 (2012), doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300391.

- Akass, E.(2019, Oktober) ”Richard Branson urges kids to leave school at 16” [Blog post]. Employee. Retrieved from https://engageemployee.com/richard-branson-urges-kids-to-leave-school-at-16/

- Vagin, M. (2019, April) ”Albert Einsteins Struggle with School”. Enlightium Academy . Retrieved from https://www.enlightiumacademy.com/blog/parent-center/entry/albert-einstein-s-struggle-with-school-1

- Polgár, L. (1989). Bring Up Genius! Budapest, H. v1.1 2017-07-31

Viktor Frankl: Maria Marshall; Edward Marshall (2012). Logotherapy Revisited: Review of the Tenets of Viktor E. Frankl’s Logotherapy . Ottawa: Ottawa Institute of Logotherapy. ISBN 978-1-4781-9377-7 . OCLC 1100192135 . Retrieved 16 February 2020 .

- Reddy, S.(2014, September 8):” Exercise Helps Children With ADHD in Study”. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/exercise-helps-children-with-adhd-in-study-1410216881

- C. G. Jung: Gesammelte Werke. 7, § 266, 404.

- “Nurtured to Be Geniuses, Hungary’s Polgar Sisters Put Winning Moves on Chess Masters” . People.com . May 4, 1987.

- “The Bell Family”. Bell Homestead National Historic Site. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- “Picasso”. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language(5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Larry R. Todd, “Mendelssohn, Felix.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 30, 2013, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/51795

- Radcliffe, (2000). The Master Musicians: Mendelssohn. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://mendelssohnincidentalmusic.weebly.com/early-development–education.html

- Cep, C. (2019, October 21): “The Real Nature of Thomas Edison’s Genius”. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/10/28/the-real-nature-of-thomas-edisons-genius

Susan Polgár

Susan Polgar (born April 19, 1969, as Polgár Zsuzsanna and often known as Zsuzsa Polgár ) is a Hungarian and American chess player. Polgár was Women’s World Champion from 1996 to 1999.

On the FIDE rating list of July 1984, at the age of 15, she became the top-ranked female player in the world. In 1991 she became the third woman to be awarded the title of Grandmaster by FIDE. She won twelve medals at the Women’s Chess Olympiad (5 gold, 4 silver, and 3 bronze).

Also a trainer, writer, and promoter, Polgar sponsors various chess tournaments for young players and is the head of the Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence (SPICE) at Webster University. She served as the Chairperson (or co-chair) of the FIDE Commission for Women’s Chess from 2008 until late 2018.

László Polgár

László Polgár (born 11 May 1946 in Gyöngyös), is a Hungarian chess teacher and educational psychologist. He is the father of the famous Polgár sisters: Zsuzsa, Zsófia, and Judit, whom he raised to be chess prodigies, with Judit and Zsuzsa becoming the best and second best female chess players in the world, respectively. Judit is widely considered to be the greatest female chess player ever as she is the only woman to have been ranked in the top 10 worldwide, while Susan became the Women’s World Chess Champion.

He has written well-known chess books such as Chess: 5334 Problems, Combinations, and Games and Reform Chess , a survey of chess variants. He is also considered a pioneer theorist in child-rearing, who believes “geniuses are made, not born”. Polgár’s experiment with his daughters has been called “one of the most amazing experiments…in the history of human education.” He has been “portrayed by his detractors as a Dr. Frankenstein” and viewed by his admirers as “a Houdini”, noted Peter Maas in the Washington Post in 1992.

Sofia Polgár

Sofia Polgar (Hungarian: Polgár Zsófia , pronounced [ˈpolɡaːr ˈʒoːfiɒ] ); born November 2, 1974) is a Hungarian, Israeli and Canadian chess player, teacher, and artist. She is a former chess prodigy.She holds the FIDE titles of International Master and Woman Grandmaster and is the middle sister of Grandmasters Susan and Judit Polgár. She lives in Israel and has worked as a chess teacher and artist.

Dr. Susan Weinschenk

Susan Weinschenk has a Ph.D. in Psychology, and is the Chief Behavioral Scientist and CEO at The Team W, Inc, as well as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point. Susan consults with Fortune 100 companies, start-ups, governments and non-profits, and is the author of several books, including 100 Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People, 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People and How To Get People To Do Stuff. Susan is co-host of the HumanTech podcast, and writes her own blog and a column for Psychology Today online. She has been interviewed for, and her work cited in media publications including The Guardian, Huffington Post, Brain Pickings, and Inc. Dr. Weinschenk’s area of expertise is brain and behavioral science applied to the design of products, services, experiences, and human interactions. Her clients include Disney, Zappos, the European Union, Discover Financial, and United Health Care. Dr. Weinschenk was a consultant on the Emmy nominated TV show Mind Field, and is a keynote speaker at conferences, including, South by Southwest (Austin Texas), Habit Summit (San Francisco), From Business to Buttons (Stockholm), and USI (Paris).

Dr. Anne Thorndike

Anne Thorndike, MD, MPH is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and an Associate Physician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, MA. She is the Director of the Metabolic Syndrome Clinic at the MGH Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Center. Her clinical and research interests are the prevention and treatment of obesity and cardiometabolic disease through lifestyle modification. Her research focuses on interventions utilizing behavioral economics strategies, such as traffic-light labels and choice architecture, to improve dietary intake and health outcomes in worksite and community-based settings. She has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, as well as several other foundations and government organizations. She currently serves on the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association, and is a member of the expert panel for the U.S. News and World Report Best Diets Rankings.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German mathematician and physicist who developed the special and general theories of relativity. In 1921, he won the Nobel Prize for physics for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. In the following decade, he immigrated to the U.S. after being targeted by the German Nazi Party.

His work also had a major impact on the development of atomic energy. In his later years, Einstein focused on unified field theory. With his passion for inquiry, Einstein is generally considered the most influential physicist of the 20th century.

Judit Polgár

Judit Polgár (born 23 July 1976) is a Hungarian chess grandmaster. She is generally considered the strongest female chess player of all time.Since September 2015, she has been inactive. In 1991, Polgár achieved the title of Grandmaster at the age of 15 years and 4 months, at the time the youngest to have done so, breaking the record previously held by former World Champion Bobby Fischer. She was the youngest ever player to break into the FIDE Top 100 players rating list, ranking No. 55 in the January 1989 rating list, at the age of 12. She is the only woman to qualify for a World Championship tournament, having done so in 2005. She is the first, and to date only, woman to have surpassed 2700 Elo, reaching a career peak rating of 2735 and peak world ranking of No. 8, both achieved in 2005. She was the No. 1 rated woman in the world from January 1989 until the March 2015 rating list, when she was overtaken by Chinese player Hou Yifan; she was the No. 1 again in the August 2015 women’s rating list, in her last appearance in the FIDE World Rankings.

She has won or shared first in the chess tournaments of Hastings 1993, Madrid 1994, León 1996, U.S. Open 1998, Hoogeveen 1999, Sigeman & Co 2000, Japfa 2000, and the Najdorf Memorial 2000.

Polgár is the only woman to have won a game against a reigning world number one player, and has defeated eleven current or former world champions in either rapid or classical chess: Magnus Carlsen, Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov, Vladimir Kramnik, Boris Spassky, Vasily Smyslov, Veselin Topalov, Viswanathan Anand, Ruslan Ponomariov, Alexander Khalifman, and Rustam Kasimdzhanov.

On 13 August 2014, she announced her retirement from competitive chess. In June 2015, Polgár was elected as the new captain and head coach of the Hungarian national men’s team. [8] On 20 August 2015, she received Hungary’s highest decoration, the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary.

Psychology exercises for you

What Are You And How Many?

Allan watts and the story of the chinese farmer, related articles.

- 15th December 2022

How To Unlock Your Hidden Potential With Logotherapy

- 14th September 2023

The Count of Monte Cristo’s Wisdom: Your Guide to Life’s Storms

- 24th December 2022

How do we regain hope after we lost all faith in the future? – A Therapy Tool From Holocaust Survivor Viktor Frankl

Tabish Nadeem

October 7, 2022 at 5:40 pm

Beautiful article.. Thanks a ton

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

FREE Habit Builder

Get my guide to tap into the power of habit formation for free.

Download the Habit Builder for free

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

How to Make Your Child a Genius: Insights from the Polgar Experiment

(1).jpg)

Imagine a modest apartment in Budapest during the 1970s, where the air is filled with the scent of home-cooked meals and the soft sound of chess pieces clinking against a wooden board. Here, three young girls sit around a table, intensely focused on their next move, guided by their father, Laszlo Polgar. This scene is the birthplace of the Polgar Experiment, a groundbreaking study that challenges the very notion of innate talent and genius.

The Genesis of the Polgar Experiment

Laszlo Polgar, a Hungarian educational psychologist, believed that geniuses are made, not born. He was convinced that with the right environment and upbringing, any healthy child could excel in any field. To test his theory, Laszlo and his wife, Klara, decided to homeschool their daughters—Susan, Sofia, and Judit—with a specialized and intensive focus on chess.

The Story Begins : Laszlo’s belief in the power of education was so strong that he declared his intention to raise geniuses even before his children were born. He meticulously planned their education and chose chess as the medium for his experiment, believing it to be an excellent tool for developing intellectual skills.

Early Days of Training

Early Exposure : From as early as they could sit up, the Polgar sisters were surrounded by chess. Laszlo created an environment rich in intellectual stimulation. Chessboards, books, and puzzles filled their home, turning it into a haven of learning and curiosity.

Structured Learning : Their education wasn't limited to chess alone. Laszlo ensured they had a well-rounded curriculum, but chess was always the centerpiece. Lessons were designed to be fun and engaging, maintaining their interest and enthusiasm. The girls were taught to view challenges as opportunities for growth, fostering a positive and resilient mindset.

Achievements of the Polgar Sisters

The results of the Polgar Experiment were nothing short of extraordinary:

- Susan Polgar : At the age of 15, Susan became the first woman to qualify for the Men’s World Chess Championship. She eventually earned the title of Grandmaster and won four Women's World Chess Championships.

- Sofia Polgar : Known for her creative and aggressive playing style, Sofia achieved the title of International Master and is remembered for her performance at the "Sack of Rome" tournament, considered one of the best in chess history.

- Judit Polgar : Often hailed as the greatest female chess player of all time, Judit became a Grandmaster at 15, breaking Bobby Fischer’s record. She was consistently ranked among the world’s top players and defeated multiple world champions, including Garry Kasparov and Viswanathan Anand.

Lessons from the Polgar Experiment

Focused Practice : Intensive and focused practice is crucial. The Polgar sisters spent countless hours practicing chess daily, refining their skills through constant repetition.

Early Development : Early exposure to a subject can ignite a lifelong passion. The sisters were introduced to chess at a very young age, which played a significant role in their success.

Parental Involvement : Active parental involvement is vital. Laszlo and Klara's commitment to their daughters' education and their supportive environment were key factors in their development.

Growth Mindset : A belief in the potential for improvement through effort is essential. The Polgar sisters were taught to view every game, win or lose, as a learning opportunity.

Inspired Experiments

The success of the Polgar Experiment has inspired other educational initiatives and studies:

- Music Prodigies : Programs like the Suzuki Method use early and intensive training to develop young musicians.

- Sports Training : Many young athletes, like those in gymnastics and tennis, undergo rigorous training from an early age, leading to professional success.

- STEM Education : Early interest and intensive practice in fields like robotics and coding through camps and competitions nurture future innovators.

The Polgar Experiment is a remarkable testament to the power of targeted education and dedicated practice. By applying these principles, you can help your child unlock their potential and achieve greatness. The key lies in starting early, maintaining focus, providing a supportive environment, and fostering a growth mindset.

- Polgar, Susan. "Chess Tactics for Champions." (Book by Susan Polgar detailing her training and chess strategies)

- ChessBase. "The Polgar Experiment – The Making of Three Chess Prodigies." Available at: ChessBase

By learning from the Polgar Experiment, you can create an environment that nurtures your child’s potential, paving the way for their future success.

Written By Dr. Jash Ajmera

Found this useful, share with others on :, read more about:.

- Skip to content

- Skip to footer

| Slow Down to the Wisdom Within

Genius Child Development: “Raise a Genius!” by László Polgár (Book Summary)

By Kyle Kowalski · Leave a Comment

This is a book summary of Raise a Genius! by László Polgár ( Free Online ).

Premium members also have access to the companion post: 🔒 How to pursue Genius Education with “Raise a Genius!” by László Polgár (+ Infographic)

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in “quotation marks” is from the author (otherwise it’s paraphrased).

- All content is organized into my own themes (not the author’s chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

About the Book & László Polgár

Socialization & society, contemporary school & potential genius, 20 characteristics of genius education, theses, principles, traits, & values, developmental ages & daily life, chess & happiness.

Genius Child Development: Raise a Genius! by László Polgár (Book Summary)

“I do not present a prescription, merely a point of view. I do not wish to exhort anyone to raise a genius. I wish to demonstrate that it is possible … I can only say that I have created something that up to now no one else has created .”

About the book:

“This book of mine appeared in Hungarian in 1989. In it I described and summarized my psychological and pedagogical experiments regarding my daughters’ and my 15-year educational experience .”

- “ I do not give a prescription, only a way of life , and I wish to persuade no one to raise geniuses. I merely wish to show that it is possible to raise geniuses .”

- “I can only pass on my pedagogical system, and guide everyone along the road that I followed, confident that it is possible and worthwhile to raise geniuses, for they can and indeed have become happy people .”

- “ The object of a pedagogical experiment can be nothing other than a person , and for their good one not only has the right, but even the duty of performing pedagogical experiments. In fact, all parents, even if not consciously, ‘experiment’ with their children. An intentional, humanistically organized experiment is much more likely to succeed .”

- “The essence of my pedagogical program is that in my opinion, every healthy child can be raised to be an outstanding person, in my words, a genius . When we began this work with my wife, we read through a large collection of books and studies. We examined the childhoods of many eminent people and noticed that all who became geniuses specialized very early in some field, and we could also document that beside them always stood a father or mother, a tutor or trainer, who were ‘obsessed’ – in the good sense of the word. So on the basis of our research we could rightly conclude that geniuses are not born: one has to raise them .”

- “The uniqueness of my experiment lies in that it is – one could say – a family group experiment, made possible by the birth of my three daughters . I have built my pedagogical optimism on this result.”

László Polgár on himself:

“I have a beautiful family, a happy marriage, three beautiful, healthy, happy, intelligent children, and I feel as well that in my work I can enjoy the pleasure of creation, for I have done something that will last. I believe that I am happy .”

- “As concerns my view of life: I have worked 15 hours a day since I was 14 . For me, quality is the main thing. I wish to do everything always at the highest level . Mediocrity, the orientation to the middle, I refuse out of principle. I strive for the summit despite obstacles .”

- “ (I’m) a person who shapes his environment, his destiny, his society, and himself . If I think through my life in my mind, I can deduce my character, my me-ness, from it. If I consider my personality traits, I can predict my destiny, because they are interrelated. Of course certain ethnic distinctives can be found in me, like over-strenuous working, over-emotionality, yearning for accomplishments, the central role of the family, the desire to develop the capabilities of my daughters, and from time to time possibly also a bit of aggression and noise.”

- “I think of myself as an honest, sincere, plain-spoken person, very sensitive about justice. I have a great love of freedom and thirst for knowledge . I am very happy that to my knowledge I have deceived no one. Regarding my work I have established very high requirements, although I also understand those people who live otherwise. Other people possibly consider me an extremist, but I prefer to call myself an optimistic realist .”

- “ I have raised my daughters to be true women . I have not only not hindered their feminization, among other things, but on the contrary: I very much expect that their psychosexual development is also normal and healthy .”

- “ I could not live otherwise than what I profess . Striving for harmony between words and actions, needing to put ideas into practice, is an integral part of my moral concept and practice.”

“In the end I would like to prove that socialization, development within society, and in that context the genius-izing of a person, depends firstly not on their native biological powers: their way of life is not decided from birth; it must be considered principally as a social product, in practice, a result of nurture . To express it provocatively, I often say, ‘Genius is not born, genius is raised .'”

Socialization:

“A healthy human has such an elastic cerebral system and flexible developmental structure that their efficacy can be developed to a high degree by pedagogical methods. The way is open for pedagogy, since children are developable, and from the viewpoint of the intellect they can be formed in any manner … Mental traits are unambiguously socially determined .”

- “ At birth every person is equal . After birth a person takes on so-called ethnic-psychological characteristics, adapting to cultural traditions and educational demands .”

- “Specific capabilities are not people’s endowments from birth, but one must make them manifest through education .”

- “One thing is certain: education also needs much more educated parents . One should devote more time to the children.”

- “ Parents and society are responsible for the development of the children’s capabilities . A large number of geniuses are lost because they themselves never learn what they are capable of.”

- “It is indeed decisive what kinds of influences reach a child in their family, what kind of example they see, in which direction they are raised – not only in what subject, but in what world view. I consider it a completely natural matter that parents will hand down their own world view: for indeed they can give nothing else .”

Society & social responsibility:

“In my conception, education is good for the individual and desirable and useful for society. A genius is a collective creation who becomes a communal treasure .”

- “A person is not born morally ready, does not bring moral values along from the womb, a maximum capability to become a moral being. But how they become, a loving family member or a hateful one, an altruist or an egoist, a humanist or a fascist – is not genetically fixed, but depends primarily on education and surroundings. As with all abilities, the moral ones can be and must be learned .”

- “Without moral values one lacks a compass for life … One should hand down in childhood fundamental moral values, which are generally human , so one does not need to restrict them, in the traditional sense, to any particular world view or political party.”

- “In my opinion genius is a notion about preserving values. I only consider those who realize socially useful actions to be geniuses … The more educated and the more talented someone is, the greater is their social responsibility .”

- “ Raising geniuses is one of the preconditions for social progress , and any society can be guided out of economic difficulty for the most part only by education and instruction.”