Advertisement

Goods and Services Tax (GST) Implementation in India: A SAP–LAP–Twitter Analytic Perspective

- Original Research

- Published: 26 January 2022

- Volume 23 , pages 165–183, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Arun Kumar Deshmukh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1839-1364 1 ,

- Ashutosh Mohan 1 &

- Ishi Mohan 2

24k Accesses

23 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In a federal structure, India's determination to much-needed fiscal reforms has been widely applauded at its face value when she relinquished her previous complex and inefficient tax regime to embrace the long-awaited Goods and Services Tax (GST). It has been a significant economic move post-independence and requires validation of facts after its introduction. The present study aims to present a general macroeconomic analysis of the extent to which the adoption of GST has improved existing tax administration and resultant general economic well-being of a democratic political economy like India in light of innovation implementation theoretical perspective. Further, the study tried to determine how the stakeholders perceived such big-bang reform even after the three years of its adoption. The study attempted to assess to what extent the adoption of GST has indeed influenced the economy in general and citizens and/or consumers in particular while using a case-based qualitative inquiry. The present research applied the situation–actor–process; learning–action–performance analysis framework for the case analysis. The facts reveal that India has observed a tremendous increase in tax base vis-à-vis revenue collection. Yet, some efforts are desired to improve the low tax to GDP ratio, skewed GST payers base, negative stakeholders’ perception of GST (revealed through Twitter sentiment analysis), and the evil of tax evasion. The other merits realized by the economy are presented as benefits to the consumers, MSMEs, improved ease of doing business ranking, and foster make-in-India and AatmanirbharBharat move by the government.

Similar content being viewed by others

Taxation transformation of businesses enabled by information systems: an empirical study of Goods and Services Tax implementation in India

Twitter Based Sentiment Analysis of GST Implementation by Indian Government

Analysis of barriers in implementation of Goods and Service Tax (GST) in India using interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The economic reforms in India after the 1990s pushed her growth as a globally integrated nation with remarkable improvements in terms of regulatory efficacy, macroeconomic stability, and geopolitical constancy (World Bank, 2019 ). Besides China in the Asian continent, India emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the last few decades (Paul & Mas, 2016 ). Fortifying the topsy-turvy yet relatively sustained growth story, India has witnessed phenomenal indirect tax reform (Chikermane, 2018 ) in the past three decades and demonstrated economic resilience by embarking upon another breakthrough in July 2017. According to the experts, after liberalizing the Indian economy in 1991, the Goods and Services Tax (henceforth GST) is a significant taxation turnaround by the Indian government (Jha, 2019 ; Siddiqui, 2018 ). India has traversed a long path to embrace GST as an excellent and long-awaited indirect tax reform aimed at one nation, one tax, and one market (GST Council, 2020a ). The global experience revealed that GST has made the business processes more efficient than ever by simplifying the tax structure and reducing the number of state and central levies (Nutman et al., 2021 ). GST is an indirect and destination-based tax. It appears to have influenced the consumers indirectly and directly impacted the businesses (Fernando & Chukai, 2018 ); however, its ripple effect is being felt across the three core sectors of the economy (Jha, 2019 ).

The complexities and inefficiencies of previous tax regimes in India (Roychowdhury, 2012 ) compelled the authorities to convert the decade-long discussion into reality. The shortcomings were primarily characterized by cascading turnover taxes between the center and states in the federal structure, making the regime less comprehensive (Rao & Chakraborty, 2010 ). The central and state levies had some inherent limitations, such as central taxes could not cover the value addition in goods outside the manufacturing stage, including a few listed services (Deloitte, 2020 ; Roychowdhury, 2012 ). To transform the indirect taxation system, GOI had introduced the long-awaited Goods and Services Tax or GST in July 2017. Sensing its magnificence, FICCI ( 2021 ) called it a big bang economic reform after independence. Despite all merits and demerits of the Indian GST implementation, little understanding exists of its influence on the economy (Kir, 2021 ) in general from the perspective of the stakeholders. Also, a little understanding was observed in the existing body of knowledge, particularly on innovation implementation in the emerging Indian public policy domain even though GST roll-out to be a process innovation in the economic system. It calls for research in the identified field about how fruitful was the introduction and implementation of GST in the economy and the response patterns of the stakeholders.

The present study aims to analyze the extent to which the implementation of GST has improved exiting indirect tax administration and the general economic state of a democratic political economy like India. The way stakeholders have perceived such big-bang economic reform after three years. A theoretical perspective of innovation implementation was applied, citing the context and knowledge gaps concerning a public policy measure in a developing economy. Thus, it attempts to answer two diverse research questions (RQs):

RQ1. How has the implementation of GST affected India's general economic scenario? and

RQ2. How have various stakeholders perceived the new tax regime?

The nature of the research questions asked determines the epistemological ground for the research (Saunders et al., 2019 ). The core aspect of questions mentioned above predominantly belongs to the interpretive paradigm, which requires selecting appropriate methods justifying constructivist ontology (Saunders et al., 2019 ). The SAP–LAP analysis-backed qualitative case-based inquiry meets the methodological and contextual requirements.

The study is organized in various sections and sub-sections comprising a literature review about GST, innovation implementation, and SAP–LAP analysis followed by research methods comprising how SAP–LAP analysis is performed with its framework to answer the above research questions. The result and discussion section elaborates the detailed analysis and interpretation of individual components of the SAP–LAP framework concerning GST implementation.

Review of Literature

This section presents a literature review about GST and indirect taxes, innovation implementation, and SAP–LAP analysis under three sub-sections followed by motivation for this research and gap analysis.

Literature on GST and Indirect Taxes

In public finance, taxes are usually collected as significant revenue sources as direct and indirect taxes. The taxes paid directly by the public, such as corporate income tax, income tax, wealth tax, are referred to as direct taxes. In contrast, indirect tax is essentially consumption-based tax such as value-added tax or VAT, service tax, and customs. The revenues from indirect taxes are shared jointly by the central and state government and some local bodies in the federal structure. In contrast, direct taxes are the central government's subject matter. France implemented GST in 1954, and the same was followed by over 100 countries, including several emerging economies such as Brazil, China, and now India (Kir, 2021 ), after observing its demonstrated success across the globe. Economists noted that a country's development hinges upon the mobilization of tax revenue (Dabla-Norris et al., 2017 ; Schlotterbeck, 2017 ). It is pertinent to ensure stable tax revenues to meet the significant budgetary heads such as healthcare, infrastructure, and education. The increasing tax revenue leads to economic growth and development (Besley and Persson, 2009 ; Gaspar et al., 2016 ; Milios, 2021 ). Also, enhancing tax collection is crucial (Akitoby et al., 2018 ; Fenochietto & Pessino, 2013 ) to attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) propounded by United Nations. Therefore, an economy is expected to have an efficient tax policy and administration. However, the tax structure differs across the continents and countries (Besley & Persson, 2009 ; Fenochietto & Pessino, 2013 ). Sindzingre ( 2007 ) pinpointed that Asian developmental states do not rely on high levels of taxation, which is characterized by their capacity to commit and intervene credibly in policies directed toward growth rather than a tax.

Research by Onaolapo et al. ( 2013 ) revealed that the adoption of value-added tax showed a statistically significant influence on revenue generation in the Nigerian context. The study also pinpointed the need for dedicated and integrated efforts from the stakeholders to improve VAT collections. The study also analyzed how value-added tax impacted revenue generation in Nigeria. They asserted that the consumption-based taxes should be assessed on different considerations such as administrative feasibility, relative revenue potential, voluntary compliance, for better implementation. These considerations also equally apply to GST implementation.

Some of the cross-sectional studies with panel data and case studies were conducted to analyze the impact of socio-political determinants, tax policy, economic dynamics, and economic structure in an economy (Garg, 2019 ; Kir, 2021 ; Kulkarni, & Apsingekar, 2021 ). Plenty of studies unveiled the relationship among factors influencing the revenue outcome while highlighting the complexities in separating the relevant determinants (Crandall & Kidd, 2006 ; Dom, 2018 , 2019 ). The study conducted by Gupta ( 2007 ) explored the relationship between economic development and the structure of the tax revenue realization in developing countries and asserted a positive correlation between per capita GDP and revenue.

Research by Dabla-Norris et al. ( 2017 ) evaluated the firm performance changes due to the tax compliance burden in 21 countries using VAT and corporate tax rates to control tax policy. Investigating the effect of tax policy changes on revenues, the study also emphasized on an association between policy reforms and revenue growth in the emerging economies (Akitoby et al., 2018 ) and maintained that policy reforms can be increased with the rising rate of indirect tax, changing the type of tax being levied, and decreasing level of exemptions. The studies measuring the impact of VAT found mixed results as some observed growth in the revenue (Ebeke et al., 2016 ; Schlotterbeck, 2017 ) while others found it insignificant (Ngoma & Krsic, 2017 ). Some studies emphasized how socio-political factors determine the extent of revenue collected relative to GDP and asserted that the Gini coefficient was negatively correlated with the revenue collections (Fenochietto & Pessino, 2013 ). Nonetheless, not enough literature could be located in the Indian context expounding implementing a tax administration policy and associated indicators.

The early research analyzing the impact of GST implementation on the Indian economy was limited and utilized only nascent and generic indicators (Bindal & Gupta, 2018 ; Dash, 2017 ; Mishra, 2018 ) to demonstrate whether GST has attained the desired outcome after implementation. The other studies were highly sectoral and regional (Garg, 2019 ; Kulkarni & Apsingekar, 2021 ). In addition, expounding the situation after the implementation of GST, The New Indian Express ( 2021 ), in its report on GST, mentioned that the government's bonafide intentions back GST yet, technical glitches and design-related flaws caused ineffective execution during its early phase. The technical malfunction also caused fake invoicing by some business enterprises. Despite all advantages, some significant implementation flaws include technical glitches, frequent changes in the rules, malfunction of input tax credit claim system, multiple tax slabs and frequent changes in items covered under these slabs, etc. (Financial Express, 2019 ; The New Indian Express, 2021 ). Many businesses have to confront multiple litigations due to a lack of clarity on various rules and their varied interpretations in different states. This aroused interest in conducting the study to unearth several theoretical and practical learnings that may lead to future research.

Having cited the above literature, the researchers observed a lack of primary and secondary literature linking indirect tax reform in an economy and its economic impact. The studies cited primarily belong to tertiary literature, which was used to establish the viewpoint. However, due to the nascent stage of GST implementation in India, it becomes difficult to deploy quantitative panel data analysis. Therefore, the study analyzed GST implementation in the economy using a factual SAP–LAP qualitative framework and Twitter sentiment analysis using the stakeholders' perception mapping. It was an exploratory inquiry to advance understanding of a less explored phenomenon with an innovation implementation-led theoretical perspective.

Literature on Innovation Implementation

Considering GST as a process innovation in a macroeconomic context, the present research cited relevant studies to analyze the status of GST after three years of implementation. The previous research on innovation implementation revolves primarily around the organizational contexts (Chung et al., 2017 ; Damanpour & Schneider, 2006 ; Dhir et al., 2020 ; Malaviya & Wadhwa, 2005 ; Singh et al., 2021a , b ), with a slight possibility for being adapted in the context of an economy. An economy akin to an enterprise needs to constantly innovate its key processes to sustain and be competitive in a contemporary environment characterized by ever-changing technology and handling of economic operations (Chung et al., 2017 ; Krawczyk-Sokolowska et al., 2021 ). Emerging economies such as India possess numerous possibilities for innovation on several fronts including the micro- and macro-level (Dhir et al., 2020 , 2021 ). Past studies have shown that innovation keeps the system competitive and is necessary to propel superior performance (Birkinshaw et al., 2008 ; Dhir et al., 2021 ).

Nevertheless, assessing the innovation-specific outcomes is intriguing in a system at both levels. It can be analyzed with its apparent characteristics, such as the effectiveness of implementation and point of innovation itself in terms of benefits derived from it (Klein & Sorra, 1996 c.f. Chung et al., 2017 ). It is asserted that approximately two-thirds of the innovations go unsuccessful and pose a financial burden on the system (Altuwaijria & Khorsheed, 2012 ). The entities implementing the invention are bound to fail to attain desired benefits due to failure of innovation or implementation (Chung et al., 2017 ).

The introduction of GST in India is a process innovation of continuous nature, depending heavily upon the principles of appropriateness, accessibility, and affordability (Fannin, 2016 ). Also, Singh and Dhir ( 2021 ) pointed that studies addressing innovation implementation focused on specific organizational contexts, including manufacturing (Dwivedi et al., 2019 ; Jamwal et al., 2019 ), Entrepreneurship (Parameswar et al., 2019 ; Singh et al., 2019 ), health (Birken et al., 2015 ; Pradhan et al., 2019 ), transportation (Shankar et al., 2019 ), financial inclusion (Malik et al., 2019 ), and ERP implementation (Nagpal et al., 2019 ). However, studies cited in the public policy domain were scanty (Singla & Hooda, 2018 ; Sushil, 2008 ; Sushil, 2019 , Suri & Sushil, 2012 ; Suri & Sushil, 2008 ). The extant literature in this field further revealed that most of the studies on innovation implementation were conducted in the developed economies and, therefore, exhibit the strategies adopted in that context, which cannot be replicated in the emerging economy scenario (Singh et al., 2021a , b ). The key differences must be thoroughly analyzed due to contextual variations in terms of demographics, infrastructural, regulatory policies, etc., for ensuring implementation of the innovation (Dhir et al., 2020 ).

Further, from the theoretical standpoint, the implementation of innovation literature has widely used dynamic capability theory to examine how the organization can adapt its knowledge base in response to environmental changes (Teece et al., 1997 ; Teece, 2018 c.f. Singh et al., 2021a , b ). The effectiveness of such implementation can be measured using the degree to which the desired outcomes are realized (Singh et al., 2021a , b ). According to Piening ( 2011 ), the implementation of an innovation, technology, or practice necessitates the creation of new routines for desired outcomes, as was the case of GST, where the government revamped all previous processes (routine). The system continuously tracks the systemic and process-related flaws in GST implementation such as technical glitches, erroneous input-tax credit claim mechanism, multiple tax slabs with frequently changing specified items. (The New Indian Express, 2021 ). The studies primarily adopted dynamic capability theory (Teece et al., 1997 ), the resource-based view (Chichkanov et al., 2021 ), grounded theory (Deloitte, 2020 ), etc., to understand the implementation. Yet, studies in public policy-related aspects are limited in numbers (Singla & Hooda, 2018 ), requiring further investigation to analyze the same. Thus, the previous literature revealed some significant research gaps in innovation implementation comprising context gap and knowledge or theory gap. The present research aims at bridging such gaps in the context of GST implementation using an SAP–LAP framework to investigate the degree to which the GST implementation as a process innovation in public policy has impacted the general state of the economy.

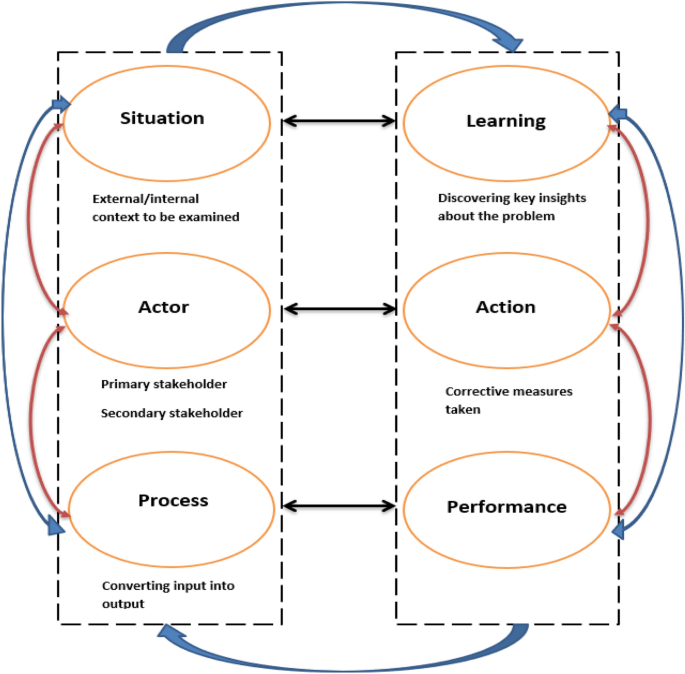

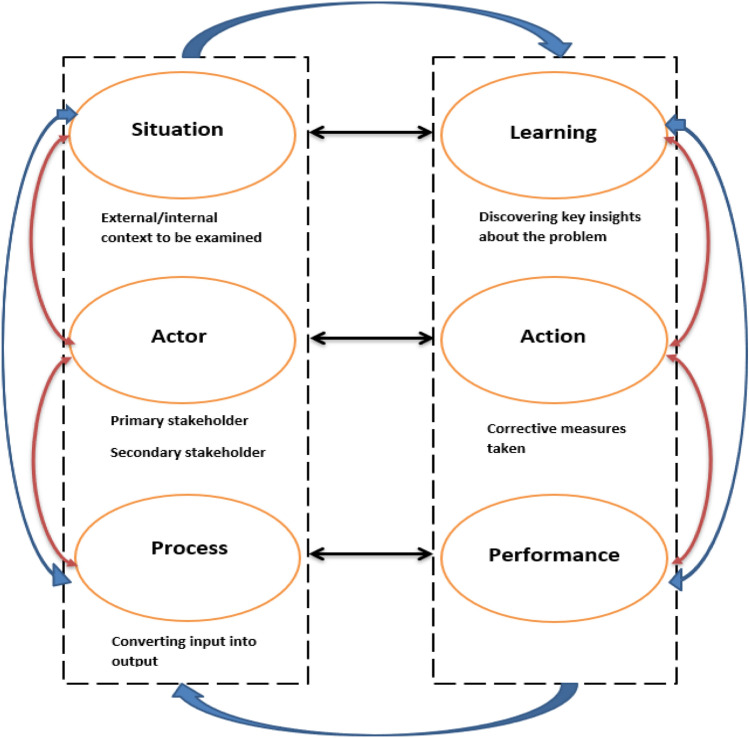

Literature on SAP–LAP Analysis

The SAP–LAP framework for analysis was initially developed by Sushil ( 2000 ) and Sushil ( 2001a ). The present study uses the SAP–LAP framework (Fig. 1 ) to analyze the pre- and post-GST implementation scenario to evaluate the system's efficacy and suggest enhancements. Several scholars in the past applied SAP–LAP analysis tools to study such situations and developed valuable solutions. The selected pioneering and prominent studies are presented in Table 1 , which exhibits the cross-context and cross-concept use of the technique.

Source : adapted from Sushil, 2014

SAP- LAP Framework.

The study utilizes a case-based review approach to analyze India's indirect taxation policy framework and associated indicators. The analysis is performed with an interpretive method known as SAP–LAP (situation, actor, process and learning, action, performance) framework developed by Sushil ( 2000 ). The SAP–LAP method was widely used by the researchers in case-based studies (Anand et al., 2018 ; Charan, 2012 ; Chavan et al., 2019 ; Kanda & Deshmukh, 2007 ; Anand et al., 2018 ; Naik & Srivastava, 2017 ; Pramod & Banwet, 2010 ; Sushil, 2019 ; Suri & Sushil, 2008 ). As described by Sushil ( 2009 ), “SAP–LAP is a generic framework which can be used in various contexts, such as problem-solving, change management, be used as generalized statements for the similar cases in the future by proper synthesis” (p. 11). SAP–LAP application has not been limited to the business verticals only but applied the least in the public policy domain (Chand et al., 2018 ; Chavan et al., 2019 ; Suri & Sushil, 2008 ).

3. Research Methods

The paper focuses on exploring the present state of GST implementation in India by the government on completing its three years. The paper follows SAP–LAP framework-based qualitative design. The study used a step-by-step approach to review extant literature to understand how the past scholars have conceptualized and theorized such a phenomenon. To critically examine the initiatives about indirect taxation and GST mainly, the authors reviewed the publications of the GST Network, Central Board of Indirect Taxes & customs (CBIC), National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, World Bank, International Monitory Fund (IMF), and relevant policy documents. An attempt was made to pinpoint the gaps and plausible implications on business and society by using the excerpts from literature and discussing with experts and stakeholders affected by GST implementation. Since the emphasis was on assuming the implementation at the last mile beside the experts, the opinions of retailers complying with GST and consumers who are indirectly paying it were considered. The existing framework gaps were recorded through 30 experts, 200 retailers, and 1000 customers. The key criterion for selecting the respondents was their direct and/or indirect involvement in GST-related regulation or compliance.

More so, to add a qualitative dimension to the SAP–LAP-based research and gauge the sentiments of different stakeholders on completion of its three years of GST, the authors have added analyses of tweets, especially as part of the situation analysis and learning synthesis. The study performs the Twitter analysis of the posts containing #GST and its associated sentiment analysis to identify how the stakeholders, including the business community vis-à-vis the common public on social media platforms, perceived the roll-out and the implementation of GST in India by the government. The researchers performed the data scrapping from Twitter with basic Tweepy (Application Programming Interface or API). The application software used in the process was NVivo (NCapture tool). It enables capturing the tweets using a #hashtag across the timelines. For this research, the restriction kept was the tweets with #GST from India. The present study captured one week's random tweets after completing three years for analysis. The purpose was to see the polarity of the sentiments after three years of GST roll-out in a random data scrapping.

SAP–LAP Analysis Framework

The SAP–LAP framework for analysis was initially developed by Sushil ( 2000 ). The expansion of the acronym SAP–LAP refers to a situation that indicates the internal and/or external environment. The external environment may include social, technological, economic, political, and natural environmental factors. In comparison, the internal environment may consist of organization-specific factors such as resources, capabilities, employees, organizational structure, and design. When considering India as an entity for analysis under this framework, the introduction of GST can be taken as a constituent of a situation aspect, and its macroeconomic, socio-political, technological impacts can be considered as the external consequences. Further, keeping the temporal orientation into account, the situation can be referred to as what has happened? what is going on? and what is expected?

The actors in the framework are people, agents, or stakeholders directly or indirectly related to the case situation under consideration. They either influence the condition or are affected by the situation. The stakeholders involved are the government, including the finance ministry, administrators, and policymakers in the GST network, business owners or managers, customers or the general public. It is indeed a highly complex web of actors in one of the largest democracies like India. The third aspect in the framework processes refers to how the situation-specific input transforms into output due to the courses of action initiated by the 'actors.' The actors enjoy the freedom of choice to transform a situation and bring about a change in the situation hand. In this context, the GST collection process, refund or input credit process, audit process, taxpayer complaint resolution process, GST council reform process, etc., are examples of various processes involved. The key actors are expected to strengthen and optimize the strategies to enhance the situation continuously.

The interaction and synthesis of the situation–actor–process framework guide the learning–action–performance framework (Sushil, 2000 , 2019 ). The first alphabet in the LAP framework stands for learning, which refers to a thorough comprehension of the core issues, problems, and challenges of SAP. It can be referred to as an outcome of the meticulous investigation of the individual components vis-à-vis the collective interplay of SAP. The learning component usually includes the generalizable output for execution or insights on specific situations or objectives. The action is all about converting the learning insights into practice to eradicate the existing systemic deficiencies. It may emphasize enhancing the current processes by improving efficiency and effectiveness.

Moreover, the action component of the framework helps in the development of some actionable policies or guidelines. The action taken will impact the performance, which can be observed through enhanced productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, higher profitability in general and better fiscal discipline, and resultant higher revenue generation in particular. It can be inferred that how flexibility in the system improves the overall performance (Evans & Bahrami, 2020 ; Sushil, 2019 ) and, as a result, how India ranks better in terms of governance, ease of doing business, and systemic transparency by applying the SAP–LAP analysis.

Results and Discussion

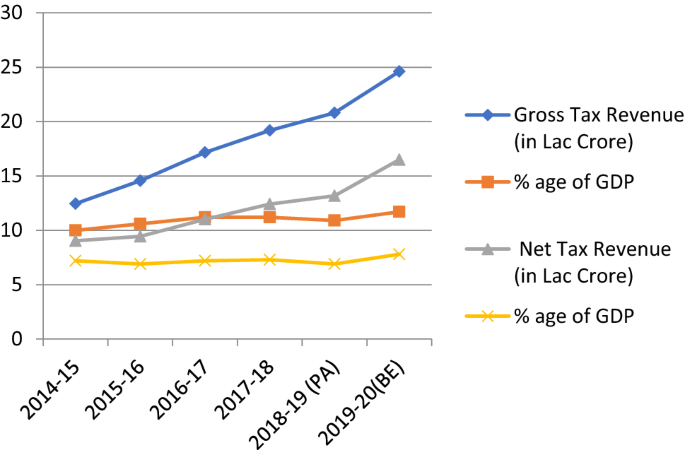

Low taxes-to-gdp ratio.

The World Bank statistics (2017–2019) on taxes as a percent of GDP reveals that India needs to increase its share of taxes in GDP at par with most of its developing counterparts. It further reported that the developed countries' ratio is greater than 10 percent compared to India’s 7.8 percent (Table 2 ) and far below the OECD average of 34% (The Economic Times, 2020 , January). This ratio indicates how well a government can finance its expenditure, reducing the borrowing. The higher proportion shows faster economic development as it enhances the government's ability to finance the expenditure.

The data obtained from the official sources were analyzed and compared with the previous tax regime to answer the first research question. The analysis is presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2 revealing the government's fiscal parameters, taxes as a percent of GDP. The answer to the second research question is addressed in the upcoming sub-section nested in case-based SAP–LAP analysis.

Source compiled from the data accessed from https://www.indiabudget.gov.in

Taxes as a percent of GDP in Post-GST Era.

Table 2 exhibits the gross and net tax revenue from 2014–2015 to 2019–2020 and their share in GDP for the corresponding year. The above data highlighted the rising revenue vis-à-vis is rising cost of collection and a corresponding reduction in the net figures from 2017 to 2018, which can be attributed to the GST implementation. In 2018–2019, the gross tax to GDP ratio was 10.9, indicating a 16 percent fall in tax revenue from the budget estimates. The reduction is due to a shortfall in GST collection (Financial Express, 2019 ). The revenue growth also corresponds to the contribution of GDP figure, which hovers between 6 and 8% for net tax revenue, far below expectations. It indicates the need for further improvement to enhance the tax revenue collections.

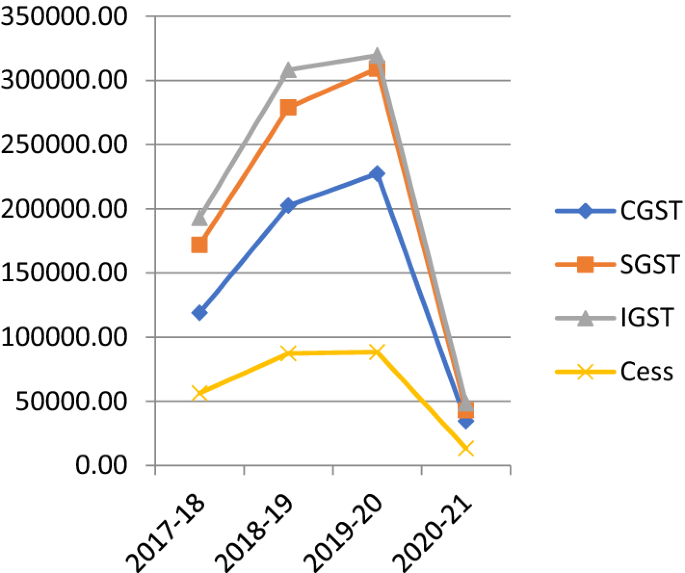

Component-Wise GST Collection

Figure 3 depicts the component-wise GST collections in the three fiscals from July 1, 2017, to June 2020. In India, the GST council divided GST into three components: Central GST or CGST, State GST or SGST, Integrated GST or IGST. The CGST represents the share of the central government, SGST indicates the state government’s claim, whereas IGST is collected on inter-state movement of goods and/or delivery of services. As shown in Fig. 3 , the collection of IGST is highest among all across the three years, followed by SGST, CGST and cess. The cess is a minor component charged along with GST in India.

Source Compiled by authors using GOI data

Component-wise GST Revenue collection.

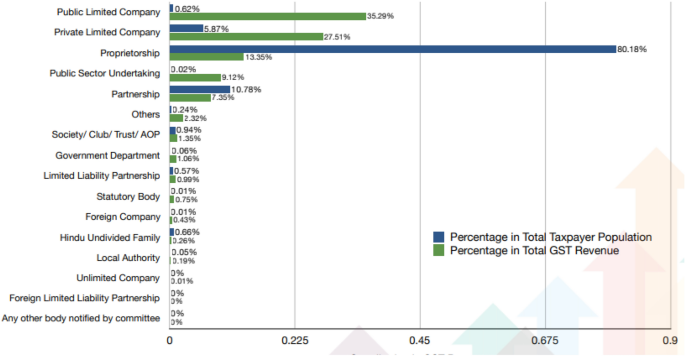

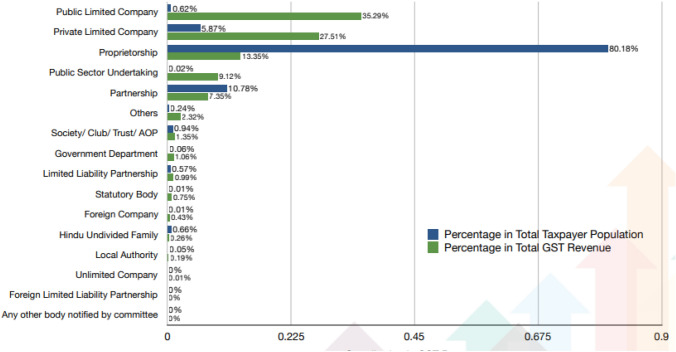

Lopsided GST Payers

The recent analysis on the contribution of various business forms in the total GST collection (Fig. 4 ) reveals that 62.8% of GST revenue comes from public and private limited companies, accounting for a meager 5.89% of the total taxpayer population. The remaining 94.11% of taxpayers contribute 37.2% of the total GST revenue. The proprietorship business holds a significant population with a GST contribution of 13.35%. The other considerable contributors are public sector undertakings (PSUs) and partnership firms. The data unfold several interesting insights for the policymakers on future policy decisions.

Source : www.gst.gov.in

GST Contribution from Different Forms of Business.

Presently, GST implementation is still in its infancy and needs several policy-level improvements to keep taxation inefficiencies and evasion at bay. The authorities should first prioritize solving the significant contributors' problem so that the flow of revenue remains unperturbed and then shift to increasing the tax base keeping the macroeconomic indicators into consideration. It will gradually enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the indirect taxation system.

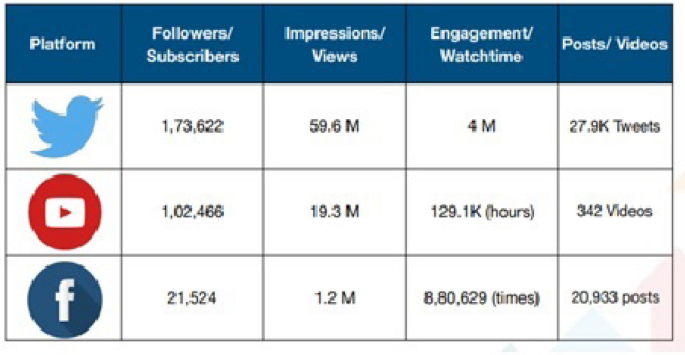

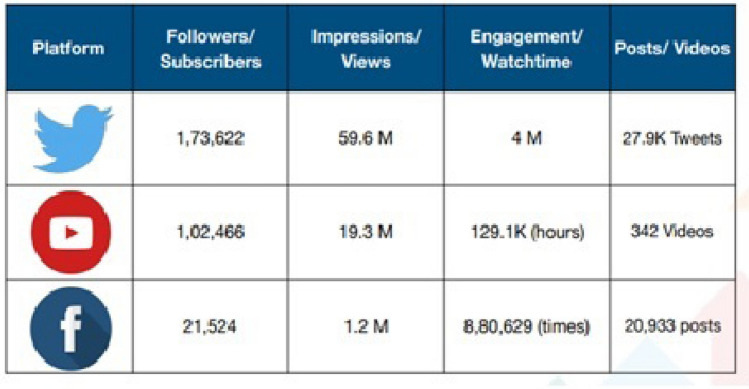

Grasp of Twitter Data

Besides the quantitative studies in the public policy domain, researchers started exploring the qualitative data generated through social media due to its ability to help decision-makers understand the acceptance of the particular policy by different stakeholders (Singh et al., 2020 ). Also, the policymakers have begun to recognize their social media presence and the responses of users and subscribers (Fig. 5 ). Several scholars such as Das and Kolya ( 2017 ), Durán-Vaca, and Ballesteros-Ricaurte ( 2019 ), and Das et al. ( 2020 ) have attempted to study the influence of the taxation-related aspects using social media analytics. Another study by Shakeel and Karwal ( 2016 ) examined the Indian union budget sentiment analysis 2016–2017. Das and Kolya ( 2017 ), Singh et al. ( 2019 ), and Das et al. ( 2020 ) primarily analyzed the Twitter data to understand the sentiment of the general public concerning GST. The startup ecosystem in India was thoroughly investigated by Singh et al. ( 2020 ) using Twitter analytics. Such studies revealed the rising trend of research using social network-based qualitative data. To assess the acceptance level of a particular phenomenon, researchers have a wide variety of choices to gather data such as interviews, surveys, and observation. However, whether positive or negative, collecting data objectively is challenging to infer. On the other hand, the data extracted from social networks reveal the polarity of likes and/or dislikes.

Source GST Council (2020b)

GST on social media.

The widely used social network-based sentiment analysis tool is Twitter analytics. It utilizes Natural Language Processing (NLP) to identify and extract personal information from multiple documents. It is capable of automatic massive tweet classification to generate positive, negative, or neutral polarity according to the language used in the text (Durán-Vaca, & Ballesteros-Ricaurte, 2019 ). It helps in knowing the emotion or opinion of the audience about the underlying subject. It is also evident through the social media statistics displayed on the official website of GST in Fig. 5 that the majority of the subscribers/followers comes from Twitter, followed by YouTube and Facebook.

As revealed in Table 3 , the sentiment analysis output indicated that a total of 1056 tweets were finally considered for analysis using NVivo. Most responses, i.e., 704 tweets, are either very negative or moderately pessimistic, while only 352 are recorded positively. Such sentiments are revealed based on the words used by the users in their tweets. Nineteen thousand one hundred ninety-seven negative comments were used to analyze the coding of terms indicated in the table. In contrast, only 7775 positive words were used concerning GST, resulting in various stakeholders' low sentiment index for GST. It also indicated that such responses might be due to a lack of awareness and reactive ones resulting from resistance to change in the transition.

The sectoral analysis showed that MSMEs face several challenges in adapting to the GST, which must be considered. As reported by experts and taxpayers, some other challenges associated with GST are long time lag in refunds, adaption and development of IT ecosystem, especially by the MSMEs, inability of the system to curb tax evasion, etc. As part of the situation analysis, the above issues and challenges require the concerned actors' action to improve.

In a federal structure, taxes are the subject matter of the union and the states. Therefore, while counting the actors, both are considered and referred to as the ‘government’ in general for the analysis. The other actors in this context are the business executives engaged in the compliance referred to here as ‘business’ and the customers who are paying the taxes indirectly and the society at large. In this tri-partite arrangement, the government is the prime actor while the latter are the complying parties. A systemic change in the name of GST necessitates the active involvement of prime actors in process design that attracts minimal resistance from the affected ones and manages the innovation implementation effectively.

The appropriation of GST is such that both center and state share equally. According to existing arrangements, for instance, if the tax rate is 18%, 9% CGST will go to the central government, whereas 9% SGST will be credited to state government accounts for intra-state transactions. On the other hand, inter-state transactions are dealt with under integrated GST or IGST in which the destination state and the central government share the revenue as mentioned above. Due to the complexity of transactions, especially when multiple states are involved in the trades, sometimes calls for more robust processes to deal with the input credit-related issues. The role of actors from government, both center and state, has become more prominent in resolving such matters. The problems related to revenue sharing and compensation to conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic intensified, for which the authorities are developing a robust mechanism. As a prime-mover, the Goods & Services Tax Council or GST Council-a constitutional body to regulate the various aspects of GST and its nationwide implementation plays a pivotal role. The Union Finance Minister of India chairs the council, and other members include the Union State Minister of Finance or Taxation of all the states. GST council along with the CBIC has played a significant role in the implementation process of GST in India.

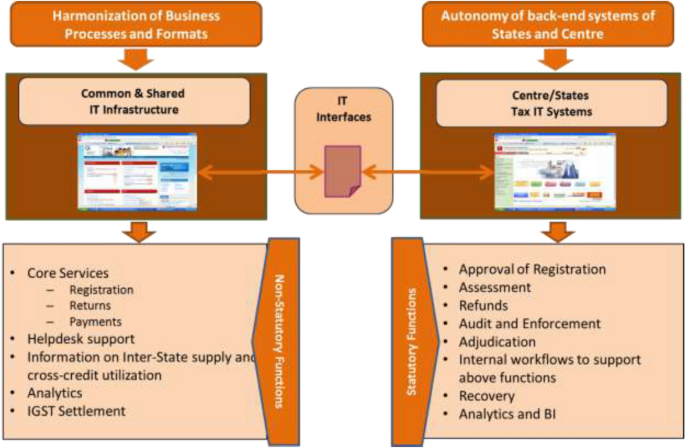

The government has taken several interventions and initiatives to improve the implementation process of GST in India. GST is the most extensive indirect tax reform in India's history, which required the integration of a nationwide diverse taxation portfolio into a single taxation system. Goods and Service Tax Network or GSTN was created to enable building a platform to meet various stakeholders' GST-related needs and smoothly facilitate the complex transaction. All the GST processes are covered under the highly diverse responsibilities of GSTN. They range from GST system application design, development and operation to IT infrastructure procurement, ensuring systemic resilience against failure and disaster, helpdesk setup and procedures, training and capacity building, backend system assessment for all the states and union territories, etc. (Fig. 6 ). Precisely, GSTN is designed to provide guidance and direction on policies and governance principles.

Source GST Council Knowledge Resources

Distribution of Work under GST.

Initially, GSTN was set up as a private company by the government but later acquired a majority stake. It provides three front-end services to the taxpayers: registration, payment, and return. The front-end solution is also assigned to develop a backend IT module for all the states/Union Territories. Infosys is selected as a Managed Service Provider or MSP for this project. A total of 73 IT/ITeS and fintech companies and one commissioner of commercial taxes (Karnataka) are impaneled as GST Suvidha Providers or GSPs to provide solutions across the nation. The role of these GSPs is to develop applications to be used by taxpayers who can facilitate interaction with GSTN. Figure 6 exhibits the work allocation under GST.

Besides process-related general measures expounded earlier, some of the specific issues addressed by the actors (primarily the government) are being highlighted as—a gradual increase in the coverage and the scope of GST in the form of inclusion and exclusion of commodities and services; revision in the coverage of various base rates keeping the consumer sensitivity into account. Likewise, the mechanism for dividing IGST collection between center and state is being negotiated by the central and the state government in the various meetings of the GST council. Accordingly, the center is working out the long-pending due to states (The Economic Times, 2020 ).

Since the government is generating the lion's share of GST revenue (63% approx.) from the public and private sector companies, their significant attention is toward resolving issues they are confronting first. The government is also developing ways to formalize the informal sectors to enhance the tax base (GST Council, 2020b ) to tame lopsided GST payers. In addition to this, the government needs a mechanism that can facilitate to meaningfully engage the stakeholders on such policy matters, which will create awareness and bust the myths being spread associated with the new fiscal policy instruments such as GST.

A detailed analysis of the situation presents several issues and challenges associated with the GST implementation, prevailing even after 3 years. Some of the critical challenges are presented in this section.

Need for More Robust IT System

For easy and speedy compliance, IT holds a significant role to play. Many companies, especially the MSMEs in the unorganized sector, lack adequate IT infrastructure. It calls for an efficient IT system for user-friendly tax administration. Presently, GSTN is serving as a particular purpose vehicle to facilitate the businesses in this, yet more selective support is desired.

Need for Skilled Human Resources

Even after three years of implementation of GST, the country is facing an acute scarcity of skilled workforce in IT and accounting. India has an adequate number of IT professionals, but a shortage of qualified accountants can help businesses deal with the new compliance norms.

Ambiguity in GST Provisions

GST subsumed 17 different levies to ease the compliance and remove the cascading effect in taxation. The system needs clarity on several aspects such as precise categorization of goods and services, and tax rates for various goods and services are yet to be fixed. Every next GST council meet comes up with newer agenda for dealing. Moreover, the shift from origin-based to destination-based taxation was not easy to implement in India's largest markets. Now, taxes are being collected based on the consumption of goods and services irrespective of their place of production, which caused a loss of revenue for industrial states. The council resolved that the central government would compensate such a loss of revenue for the initial few years. Also, there has been a demand from several pressure groups to bring high revenue items such as petrol, petroleum products, and alcohol under the ambit of GST, which is still under discussion.

Tackling the RNR Conundrum

It is challenging for the government to balance inflation and net revenue loss to attain an optimal revenue-neutral rate or RNR. RNR is referred to as a rate at which the government's revenue through the new tax regime (GST in this case) will be equal to the preceding taxation regime. It directly affects the fiscal policy and inflation rate (Kumar et al., 2018 ). The higher RNR causes a loss of competitive edge for India domestically vis-à-vis globally (Bhattacharya, 2017 cited from Kumar et al., 2018 ). The higher cost will push inflation and, in turn, badly affect the purchasing power. Narula ( 2016 ) asserted that RNR is one of the most significant GST implementation challenges and maintains that the government should ensure no revenue loss while adopting to a new taxation regime.

Lack of Awareness Among the Stakeholders

The Twitter sentiment analysis revealed that many stakeholders perceived the roll-out of GST negatively. One of the reasons could have been the lack of proper awareness about the new tax regime. Lourdunathan and Xavier ( 2017 ) suggested that India, a democratic country, should clarify its citizens about the recent amendments. Due to a lack of awareness, the citizens sometimes pay more taxes than required, especially in the rural areas and subsequent knowledge of which leads them to wear a negative perception of the tax regime.

After thoroughly analyzing the situation and the process, discussing the actions initiated to improve GST implementation is pertinent. The government of India, through GST council and CBIC backed by GSTN, has ensured the following changes.

Flexibility and Simplification of Compliances

The authorities have allowed taxpayers to comply during the transition by extending the deadline for filing returns and reconciliation by introducing the simplified return filing system and the nationwide e-way bill. The AI-based chatbot GITA or GST Interactive Technical Assistant trains the taxpayers' interaction easily and speedily. This way, the website visitors can interact and settle their issues without much workforce involvement after the introduction of the facility in June 2020.

Relief to MSMEs

The extension in registration threshold limit, introduction and extension of composition scheme to service providers have been taken well by the taxpayers, which proved to be a significant relief measure for MSMEs. Moreover, offering speedy solutions to the MSMEs' issues, GoI has already constituted a Group of Ministers (GoM) that thematically takes account of the situation in this regard. In another move, it was decided by the government that GSTN would provide free accounting and billing software to small taxpayers.

Rationalization of GST Rates

The rates of GST were decided considering the nature of commodities. Some of the entities classified as necessities were suitably reviewed and moved from the high tax bracket (18–28%) to the low-tax bracket, which several stakeholders took as a welcome move. In the 36th meeting of the GST Council in July 2019, the rate rationalization moves to emphasize and promote clean energy by council. The council decided to reduce the GST rates on electric vehicles from 12 to 5% and charger/charging stations from 18 to 5%.

Mobilization of Revenue

A Group of Ministers or GoM was constituted to study the revenue trend and assess the underlying reasons behind structural patterns influencing the revenue collection in some states. It would include looking at plausible reasons behind the deviation of the revenue collection targets from basic assumptions.

E-Way Bill System for Efficient Compliance

The GST council introduced an electronic way or e-way bill system from April 1, 2018, initially for all inter-state movement of goods that now covers intra-state movements. This initiative aimed to allow the movement of goods across the nation, which resulted in hassle-free transportation. The E-way bill was a monumental shift from the departmental policing model to the self-declaration model, reducing high administration costs.

Some Penal Measures

From August 21, 2018, the council decided to have a system barring the generation of the e-way bill if a recipient or supplier does not file a GST return for two consecutive tax periods. It resulted in regularity and timeliness of compliance by the taxpayers.

Anti-profiteering Mechanism by Establishing National Anti-profiteering Authority (NAA)

It was also observed that in many countries, GST implementation resulted in an inflationary trend despite a provision of an input tax credit. The meticulous analysis revealed that it has happened because of the non-passing of the benefits to the consumers by suppliers involved in the profiteering. Ideally, the benefit of increased input tax credit or decrease in tax rate should pass to the recipient. When it does not pass to the recipient, it is treated as illegal profiteering. The central government constituted NAA to examine the non-passing of the benefits of reduced tax incidence or increase in input tax credit under GST.

Composition Scheme for Small Business and Services Suppliers

The scheme envisaged for the small businessmen who are a supplier of goods and restaurant services. In this, business with turnover up to Rs. 1.5 crore required to pay taxes equal to 1–5% on the turnover and required to make quarterly payments from FY 2019–2020 and file the return annually. In the case of service suppliers, a person has a turnover of up to Rs. 50 lakh to pay a tax equal to 6 percent on the turnover and required to pay quarterly with the annual filing of the returns.

The Mechanism for Government Accounts Settlement

Periodic account settlement between Centre and State is done. Adjustments and differences related to SGST and IGST are considered so that both center and the state get their due share of tax revenues. The fund transfer is done based on the information contained in the returns filed.

Capacity Building Efforts by CBIC

The CBIC has played a significant role in drafting GST law, especially IGST and CGST law under the center’s purview. With the rising number of taxpayers, CBIC has also suitably scaled up its IT infrastructure to deal with massive data and other related challenges. CBIC is working on an ambitious project worth Rs. 2256 crore for re-engineering its existing software and planning to replace it with all new ‘SAKSHAM’ for GST. Such capacity-building initiatives facilitate the smooth transition in the innovation implementation saga at the macroeconomic level.

Performance

Having analyzed the situation, actors, processes, the authors presented learning and action taken. The present section deals with specific aspects of the action taken, which enhanced the performance. The performance analysis can be taken as benefits being realized by various stakeholders in the economy.

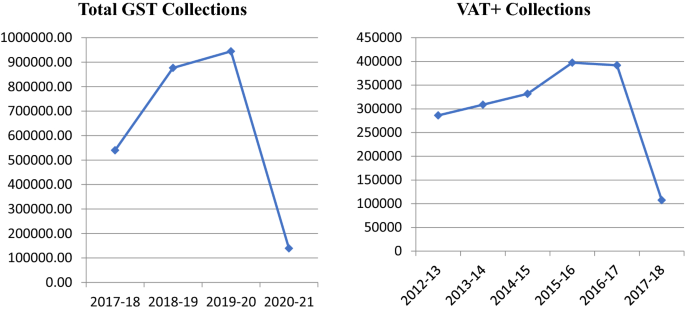

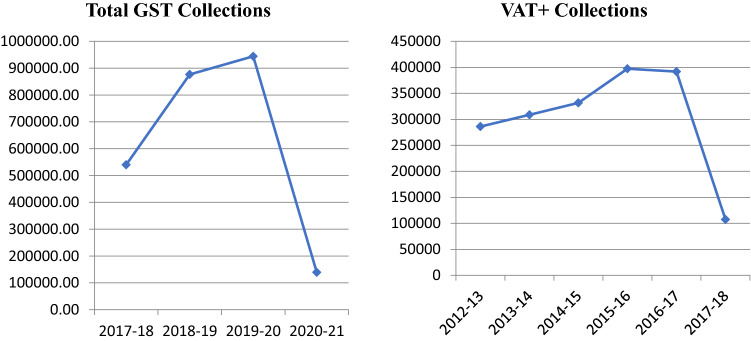

VAT and GST: Comparison of Two Regimes

Table 4 presents a precise comparison of the total collections of the two tax regimes, i.e., pre-GST era up to June 2017, where the taxpayers have to comply with a multiplicity of taxes and post-GST era wherein GST subsumed the other taxes with effect from July 2017 onward. In the pre-GST regime, payers have to comply with significant taxes such as value-added tax or VAT, service tax, central sales tax or CST, octroi and 14 more such state and local levies. The comparison explicitly reveals a sharp upswing in GST revenues between 2017 and 2020 compared with the taxes collected between 2014 and 2017. For instance, if the revenue figures for 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 are to be compared, there is a sharp rise of more than 30 percent. Similarly, the collections for 2018–2019 record growth of more than 60% over the previous fiscal (Fig. 7 ). The increase in the revenue also points out toward the widening tax base and reducing tax evasion incidences.

Revenue comparison between GST and VAT + Taxes (in Rs. Crore)

The difference is vast, which is higher even after accounting for corresponding inflation and GDP growth rate. The data presented for the year 2017–2018 represent the tax revenues for only one quarter (April–June 2017) as this was the final quarter of the previous tax regime. Likewise, the data indicated for 2020–2021 is also for a single quarter (April–June 2020). The data also demonstrates a sudden decline in revenues through GST in the quarter due to the COVID-19 nationwide lockdown and the resultant extension of the deadlines by the government, which may exhibit a hike in the next quarter. The GST figures include central GST, state GST, integrated GST, and cess, a revenue-sharing mechanism designed by the GST council in India.

Benefits for the Consumers

The removal of cascading effects in preceding tax regimes (CENVAT, state VAT, service tax, etc.) has benefited the consumer the most. Consequently, the prices of several products have come down considerably. The reduced prices have contributed to more consumer surplus and may accumulate greater purchasing power soon.

Performance on Ease of Doing Business

The one nation, one tax, one market formula to bring uniformity and simplicity, GST reduced multiple taxes and fewer exemptions. The compliance cost also came down significantly with the unification of the tax regime. It also resulted in convenient record-keeping and gradually automated compliance through the processes such as registration, return, and refund. All interactions are routed through the GSTN portal resulted in lesser public interference between tax administration and taxpayers. Due to the online filing of returns, the compliance environment has improved.

Such online processes have reduced the dependency on time-consuming paperwork and contributed to building a more robust taxation system. Moreover, it led to quicker online verification of input credit. These endeavors collectively enhanced India's position in the World Bank's ease of doing business performance index by 79 positions from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2019 (IBEF, 2020 ).

Benefits to MSMEs and New Entrepreneurs

With an increase in GST registration threshold for small businesses having annual aggregate turnover of more than rupees forty lakhs in the case of goods suppliers and rupees twenty lakhs in the case of service suppliers. A single registration is required under GST, which is more straightforward than the previous regime of multiple compliances. The composition scheme for some businesses has also proved beneficial for several firms.

Fostering Make in India and Aatmanirbhar Moves

GST led to creating a unified common market, which attracted investment from foreign players as well as national corporations in various industries, which led to pursuing the Make in India initiative and AatmanirbharBharat (Self-reliant India) move for the government. Barring a few short-term exceptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, India observed an aggregate demand boost. However, the rise in manufacturing activity and employment could not be attained as expected before the GST introduction. It has gainfully improved the country's overall investment climate, and it will subsequently benefit the states.

Implications and Conclusion

GST is assumed to be significant indirect tax reform to propel the economic growth engine, promisingly replacing the intriguingly complex and multi-layers taxation regime with a much simpler, transparent, and tech-driven administration. The present study's analysis revealed that the benefits observed due to its implementation would remove the impediments to inter-state trade and thereby project India as a common market and realize the vision of one nation, one tax, and one market. The study indicates that GST implementation is on its way to attaining the set objectives of unification of the Indian market, simplifying the compliance procedure, and enhancing the tax base to finance the developmental aspiration of the nation. The outcomes indicated that the GST being a process innovation has been implemented well hitherto with some temporal adjustments as the effectiveness of implementation hinges on the extent to which the stated objectives are attained, which is consistent with the implementation-related study by Singh et al. ( 2021a , b ). However, it is too early to say that introduction of GST has led to the attainment of these targets yet the preliminary analysis illustrates that it has been a promising move. It is evident through some of the key economic indicators mentioned in the SAP–LAP analysis that within the short span of the GST regime, the government could expand its tax base without hurting the stakeholders' sentiment and attain a much better ranking on the ease of doing business while nurturing MSMEs. Additionally, the processes involved, such as GST collection, refund or input credit, audit process, GST council reforms, GST Network, taxpayers' complaints, require continuous improvement and time bound re-engineering to meet changing business requirements.

The LAP synthesis revealed first the situation-based learning, which demands a robust IT system to tame the evaders and miscreants such as recent fake invoicing fiasco. It has reduced the chances of error and enhanced faceless and timely verification. The frequent changes in the GST provisions, on the one hand, offer flexibility, but at the same time, it causes troublesome transactions for the enterprises. As revealed from the Twitter sentiment analysis results that the stakeholders exhibited a declivity toward the GST implementation, which can be the outcome of lack of awareness and a typical tendency of inherent resistance to change for the new system. The innovation implementation literature also necessitates the constructive engagement of the stakeholders to ensure its success which is consistent with the study by Chung et al. ( 2017 ).

The action taken includes the introduction of flexibility and simplicity in the compliance mechanism as and when desired. The e-way bill system also facilitated efficient compliance and partially overcame the issues related to tax evasion. Nonetheless, the GST regime should establish a robust design with solid checks and balances to eradicate the evaders and promote good tax governance ultimately. Furthermore, the capacity-building efforts by the CBIC are yet to show up the outcomes which may be public after the implementation of the ambitious SAKSHAM system. The performance analysis explicitly exhibited the superiority of the GST regime over the past VAT regime on several dimensions. The GST implementation has immensely benefitted the consumers, MSMEs, and new enterprises by removing multiple compliance requirements through process simplification and thereby improving India's ease-of-doing-business ranking. To achieve the ambitious Make-in-India and Aatmanirbhar Bharat goals, GST can prove to be a gamechanger, provided the efforts are directed toward eradicating the systemic loopholes.

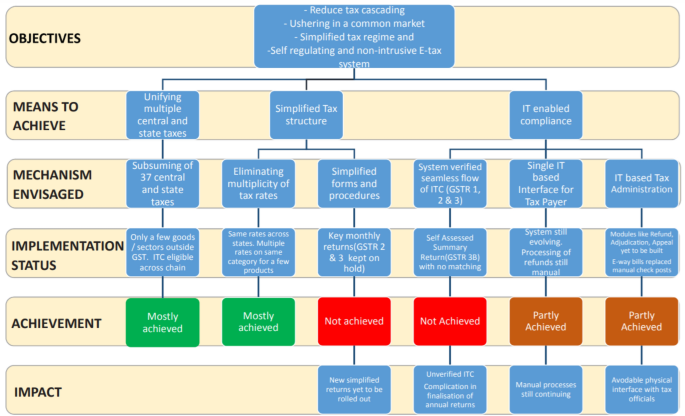

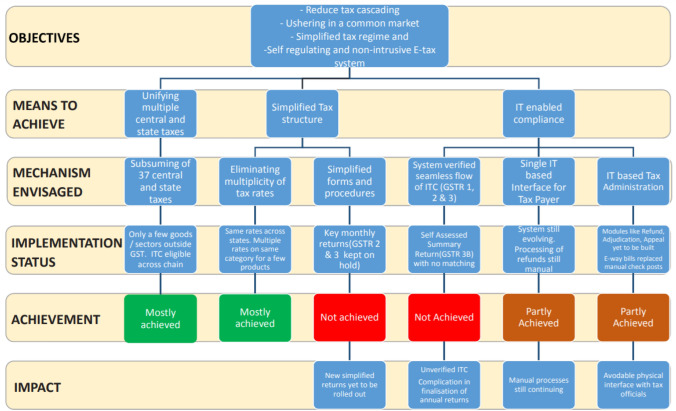

The theoretical implications of the study are evident through its propensity to address the knowledge gap encompassing an exploratory case-based inquiry linking GST implementation and economic scenario in the Indian context. It also established that the implementation issues require constant supervision and immediate action. The findings drawn from SAP–LAP analysis are also consistent with the report conceptualized by CAG ( 2019 ) presented through Fig. 8 is self-explanatory, exhibiting the extent to which the objectives of GST roll-out are attained. It mentions that the two significant market objectives, unification and simplification of the tax structure, have been achieved well except with a slight fallout on simplified form and procedure. However, the other objective about IT compliance is partially completed with some fallout. The actors must make a collaborative endeavor (Singh and Dhir, 2021 ) to create a simplified IT-enabled process to attain the last and most important objective (Fig. 8 ). Although such problems are expected during the transition phase of implementation through IT as observed in the previous research by Anand et al. ( 2018 ), Suri ( 2005 ), Suri and Sushil ( 2012 ), and Suri and Sushil ( 2008 ), which are commonly related to implementation hurdles due to ineffective change management strategies (Siddiqui, 2018 ; Singh et al., 2020 ).

Source CAG, 2019 — https://cag.gov.in/

Objectives of GST roll-out, achievement, Impact, and fallout.

Furthermore, the study advances an understanding of how SAP–LAP analysis can analyze the fiscal policy issues applying a blended method approach to establish a multi-stakeholder perspective on GST implementation through Twitter analytics coupled with SAP–LAP. Future studies may advance such a combined perspective to draw more inclusive research outcomes. The study also highlighted the social networking site such as Twitter as a powerful medium to meaningfully connect with the stakeholders in policy implementation at large. Also, the study advanced the understanding of innovation implementation research from enterprise context to the macroeconomic context for an economy which may be taken as an incremental extension of theoretical knowledge on policy execution. Nonetheless, the present study, primarily qualitative, neither delves upon the impact of GST implementation on the macroeconomic and fiscal parameters nor attempted to analyze it on any specific microeconomic indicator. Also, GST implementation in India is still in the introduction phase; therefore, not enough panel data could be generated to establish the relationship between GST tax reform and economic growth using econometric modeling. Future studies can show the relationship between the two indicators using quantitative or econometric modeling to ensure the broader generalizability of the findings. More so, the effectiveness of the GST implementation can be measured by quantitatively comparing the set objectives with several fiscal indicators.

Key Questions

How has the implementation of GST affected India's general economic scenario?

How have various stakeholders perceived the new tax regime?

Akitoby, M. B., Baum, M. A., Hackney, C., Harrison, O., Primus, K., & Salins, M. V. (2018). Tax revenue mobilization episodes in emerging markets and low-income countries: Lessons from a new dataset. International Monetary Fund.

Altuwaijria, M. M., & Khorsheed, M. S. (2012). InnoDiff: A project-based model for successful IT innovation diffusion. International Journal of Project Management, 30 , 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.04.007

Article Google Scholar

Anand, R., Medhavi, S., Soni, V., Malhotra, C., & Banwet, D. (2018). Transforming information security governance in India (A SAP–LAP-based case study of security, IT policy and e-governance). Information and Computer Security, 26 (1), 58–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/ics-12-2016-0090

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2009). The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. American Economic Review, 99 (4), 1218–1244.

Google Scholar

Bhattacharya, G. (2017). Evaluation and implementation of GST in Indian growth: A study. International Journal of Commerce and Management Research, 3 (11), 65–68.

Bindal, M., & Gupta, D. C. (2018). Impact of GST on Indian Economy. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research (IJEMR), 8 (2), 143–148.

Birken, S. A., Lee, S. Y. D., Weiner, B. J., Chin, M. H., Chiu, M., & Schaefer, C. T. (2015). From strategy to action: How top managers’ support increases middle managers’ commitment to innovation implementation in healthcare organizations. Health Care Management Review, 40 (2), 159.

Birkinshaw, J., Hamel, G., & Mol, M. J. (2008). Management innovation. Academy of Management Review, 33 , 825–845. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.34421969

CAG. (2019). Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India https://cag.gov.in/uploads/download_audit_report/2019/Report_No_11_of_2019_Compliance_Audit_of_Union_Government_Department_of_Revenue_Indirect_Taxes_Goods_and_Services_Tax.pdf

Chand, P., Thakkar, J. J., & Ghosh, K. K. (2018). Analysis of supply chain complexity drivers for Indian mining equipment manufacturing companies combining SAP–LAP and AHP. Resources Policy, 59 , 389–410.

Charan, P. (2012). Supply chain performance issues in an automobile company: A SAP–LAP analysis. Measuring Business Excellence, 16 (1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/13683041211204680

Chavan, M., Chandiramani, J., & Nayak, S. (2019). Assessing the state of physical infrastructure in progressive urbanization strategy: SAP–LAP analysis. Habitat International, 89 , 102002.

Chichkanov, N., Miles, I., & Belousova, V. (2021). Drivers for innovation in KIBS: Evidence from Russia. The Service Industries Journal, 41 (7–8), 489–511.

Chikermane, G. (2018). 70 Policies that Shaped India 1947 to 2017, independence to $2.5 Trillion. Observer Research Foundation. Accessed on October 2021 from https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/70_Policies.pdf

Chung, G. H., Choi, J. N., & Du, J. (2017). Tired of innovations? Learned helplessness and fatigue in the context of continuous streams of innovation implementation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38 (7), 1130–1148.

Crandall, W. J., & Kidd, M. (2006). Revenue authorities: Issues and problems in evaluating their success. Accessed on September 10th, 2020 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=944078

Dabla-Norris, M. E., Misch, F., Cleary, M. D., & Khwaja, M. (2017). Tax administration and firm performance: New data and evidence for emerging market and developing economies. International Monetary Fund.

Damanpour, F., & Schneider, M. (2006). Phases of the adoption of innovation in organizations: Effects of environment, organization and top managers 1. British Journal of Management, 17 (3), 215–236.

Das, S., & Kolya, A. K. (2017). Sense GST: Text mining & sentiment analysis of GST tweets by Naive Bayes algorithm. In 2017 third international conference on research in computational intelligence and communication networks (ICRCICN) (pp. 239–244). IEEE.

Das, S., Das, D., & Kolya, A. K. (2020). An approach for sentiment analysis of GST tweets using words popularity versus polarity generation. In Computational intelligence in pattern recognition (pp. 69–80). Springer, Singapore.

Dash, A. (2017). Positive and negative impact of GST on Indian economy. International Journal of Management and Applied Science, 3 (5), 158–160.

Deloitte (2020) Three years of GST Journey so far and the way forward. https://www2.deloitte.com/in/en/pages/tax/articles/three-years-of-gst.html

Dhir, S., Ongsakul, V., Ahmed, Z. U., & Rajan, R. (2020). Integration of knowledge and enhancing competitiveness: A case of acquisition of Zain by Bharti Airtel. Journal of Business Research, 119 , 674–684.

Dhir, S., Rajan, R., Ongsakul, V., Owusu, R. A., & Ahmed, Z. U. (2021). Critical success factors determining performance of cross-border acquisition: Evidence from the African telecom market. Thunderbird International Business Review, 63 (1), 43–61.

Dom, R. (2018). Taxation and accountability in sub-Saharan Africa . Working Paper 544. London: Overseas Development Institute. [MM].

Dom, R. (2019). Semi-autonomous revenue authorities in sub-Saharan Africa: Silver bullet or white elephant. The Journal of Development Studies, 55 (7), 1418–1435.

Durán-Vaca, M. K., & Ballesteros-Ricaurte, J. A. (2019). Sentiment analysis on twitter to measure the perception of taxation in Colombia. In In International conference Europe Middle East & North Africa information systems and technologies to support learning (pp. 184–193). Springer, Cham.

Dwivedi, A., Agrawal, D., & Madaan, J. (2019). Sustainable manufacturing evaluation model focusing leather industries in India: A TISM approach. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 10 (2), 319–359.

Ebeke, C., Mansour, M., & Rota-Graziosi, G. (2016). The Power to Tax in Sub-Saharan Africa: LTUs, VATs, and Saras.

Economic Survey. (2020–21). Chapter 2: Fiscal Development, pp. 51–89. Accessed on December 2nd, 2020 from https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/doc/vol2chapter/echap02_vol2.pdf

Evans, S., & Bahrami, H. (2020). Super-Flexibility in Practice: Insights from a Crisis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management , 21 (3), 207–214.

Fannin, R. A. (2016). Innovation in Emerging Markets: Asia. In Innovation in emerging markets (pp. 51–71). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Fenochietto, M. R., & Pessino, M. C. (2013). Understanding countries’ tax effort (No. 13–244). International Monetary Fund.

Fernando, Y., & Chukai, C. (2018). Value co-creation, goods and service tax (GST) impacts on sustainable logistic performance. Research in Transportation Business and Management, 28 , 92–102.

FICCI. (2021). Economy Wrap. Accessed on October 11th, 2021 from https://ficci.in/sector/report/21914/news_wrap_sep16.pdf

Financial Express. (2019). Economic Survey 2019: Taxes not keeping up pace with growth as GST collection falls short of target. Accessed on October 20th, 2020 from https://www.financialexpress.com/budget/economic-survey-2019-taxes-not-keeping-up-pace-with-growth-as-gst-collection-falls-short-of-target/1628594/

Garg, N. (2019). Impact of GST on various sectors of Indian economy. Research Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary, 4 (3), 668–673.

Gaspar, V., Jaramillo, L., & Wingender, M. P. (2016). Tax capacity and growth: Is there a tipping point? International Monetary Fund.

GST Council. (2020a). GST Reports. Accessed on September 14th, 2020 from http://www.gstcouncil.gov.in/

GST Council. (2020b). GST in media. Retrieved June 9th, 2020, from http://gstcouncil.gov.in/

Gupta, A. S. (2007). Determinants of tax revenue efforts in developing countries (No. 7–184). International Monetary Fund.

IBEF (2020) Economic Survey—2019–20. Accessed on October 31st, 2020 from https://www.ibef.org/economy/economic-survey-2019-20

Iyengar, V., Behl, A., Pillai, S., & Londhe, B. (2016). Analysis of palliative care process through SAP–LAP inquiry: A case study on Palliative Care and Training Centre. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 17 (4), 403–416.

Jamwal, A., Aggarwal, A., Gupta, S., & Sharma, P. (2019). A study on the barriers to lean manufacturing implementation for small-scale industries in the Himachal region (India). International Journal of Intelligent Enterprise, 6 (2–4), 393–407.

Jha, R. (2019). Modinomics: Design, implementation, outcomes, and prospects. Asian Economic Policy Review, 14 (1), 24–41.

John, L., & Ramesh, A. (2012). Humanitarian supply chain management in India: An SAP‐LAP framework. Journal of Advances in Management Research .

John, L., & Ramesh, A. (2012a). Humanitarian supply chain management in India: An SAP–LAP framework. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 9 (2), 217–235.

Kabra, G., Ramesh, A., & Arshinder, K. (2015). Identification and prioritization of coordination barriers in humanitarian supply chain management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 13 , 128–138.

Kanda, A., & Deshmukh, S. G. (2007). Supply chain coordination issues: an SAP-LAP framework. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics , 19 (3), 240. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555850710772923 .

Kir, A. (2021). India’s goods and services tax: A unique experiment in cooperative federalism and a constitutional crisis in waiting. Canadian Tax Journal, 69 (2), 391–445.

Klein, K. J., & Sorra, J. S. (1996). The challenge of innovation implementation. Academy of Management Review, 21 , 1055–1080. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1996.9704071863

Krawczyk-Sokolowska, I., Pierscieniak, A., & Caputa, W. (2021). The innovation potential of the enterprise in the context of the economy and the business model. Review of Managerial Science, 15 (1), 103–124.

Kulkarni, S., & Apsingekar, S. (2021). A Study of Impact of GST on Indian Economy with Reference to Pune Region (No. 6132). EasyChair .

Kumar, P. S., & Anbanandam, R. (2020). Theory building on supply chain resilience: A SAP–LAP Analysis. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management , 1–21.

Kumar, P., Haleem, A., Qamar, F., & Khan, U. (2018). Analysis of maiden modal shift in coal transportation supply chain using SAP–LAP technique. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, 30 (4), 458–476.

Lourdunathan, F., & Xavier, P. (2017). A study on implementation of goods and services tax (GST) in India: Prospects and challenges. International Journal of Applied Research, 3 (1), 626–629.

Mahajan, R., Garg, S., & Sharma, P. B. (2013). Frozen corn manufacturing and its supply chain: Case study using SAP–LAP approach. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 14 (3), 167–177.

Majumdar, S. K., & Gupta, M. P. (2001). E-business strategy of car industry: SAP–LAP analysis of select case studies. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 2 (3), 13–28.

Malaviya, P., & Wadhwa, S. (2005). Innovation management in organizational context: an empirical study. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management , 6 (2), 1–14.

Malik, S., Maheshwari, G. C., & Singh, A. (2019). Understanding financial inclusion in India: A theoretical framework building through SAP–LAP and efficient IRP. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20 (2), 117–140.

Milios, L. (2021). Towards a circular economy taxation framework: Expectations and challenges of implementation. Circular Economy and Sustainability , 1–22.

Mishra, N. (2018). Impact of GST on Indian economy. International Journal of Basic and Applied Research, 8 (11), 385–389.

Nagpal, S., Khatri, S. K., & Kumar, A. (2019). Ensuring quality in ERP implementations through testing components: an ISM approach. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management , 19 (1), 89–103.

Naik, S., & Srivastava, M. (2017). A study on relevance of professional training to healthcare housekeeping aide through SAP–LAP inquiry. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development, 8 (4), 743. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2017.00425.9

Narula, C. A. (2016). GST—A milestone in Indian tax regime. International Journal in Multidisciplinary and Academic Research, 5 (6), 1–8.

Ngoma, M. M., & Krsic, N. (2017). Assessing the impact of tax administration reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Nutman, N., Isa, K., & Yussof, S. H. (2021). GST complexities in Malaysia: Views from tax experts. International Journal of Law and Management.

Onaolapo, A. A., Aworemi, R. J., & Ajala, O. A. (2013). Assessment of value-added tax and its effects on revenue generation in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4 (1), 220–225.

Parameswar, N., Hasan, Z., Dhir, S., & Ongsakul, V. (2019). Factors that drive development of technological entrepreneurship in South Asia. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 12 (3), 429–448.

Paul, J., & Mas, E. (2016). The emergence of China and India in the global market. Journal of East-West Business, 22 (1), 28–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669868.2015.1117034

Piening, E. P. (2011). Insights into the process dynamics of innovation implementation: The case of public hospitals in Germany. Public Management Review, 13 (1), 127–157.

Pradhan, R., Sagar, M., Pandey, T., & Prasad, I. (2019). Consumer health risk awareness model of RF-EMF exposure from mobile phones and base stations: An exploratory study. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 16 (1), 125–145.

Pramod, V., & Banwet, D. (2010). System modeling of telecom service sector supply chain: A SAP–LAP analysis. International Journal of Business Excellence, 3 (1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbex.2010.029486

Rao, R. K., & Chakraborty, P. (2010). Goods and services tax in India: An assessment of the base. Economic and Political Weekly , 49–54.

Ravi, V., & Shankar, R. (2006). Reverse logistics operations in paper industry: A case study. Journal of Advances in Management Research .

Roychowdhury, P. (2012). Vat and GST in India—A note. Paradigm, 16 (1), 80–87.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students , eighth edition.

Schlotterbeck, S. (2017). Tax administration reforms in the Caribbean: Challenges, achievements, and next steps. International Monetary Fund.

Shakeel, M., & Karwal, V. (2016). Lexicon-based sentiment analysis of Indian Union Budget 2016–17. In 2016 International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC) (pp. 299–302). IEEE.

Shankar, R., Pathak, D. K., & Choudhary, D. (2019). Decarbonizing freight transportation: An integrated EFA-TISM approach to model enablers of dedicated freight corridors. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 143 , 85–100.

Shukla, R. K., Garg, D., & Agarwal, A. (2011). Study of select issues related to supply chain coordination: Using SAP-LAP analysis framework. Global Journal of Enterprise Information System , 3 (2), 56–69.

Siddiqui, K. (2018). The political economy of India’s economic changes since the last century. Argumenta Oeconomica Cracoviensia, 19 , 103–132.

Sindzingre, A. (2007). Financing the developmental state: Tax and revenue issues. Development Policy Review, 25 (5), 615–632.

Singh, P., Sawhney, R. S., & Kahlon, K. S. (2019). Twitter-based sentiment analysis of GST implementation by Indian government. In Digital business (pp. 409–427). Springer, Cham.

Singh, S., Chauhan, A. and Dhir, S. (2020). Analyzing the startup ecosystem of India: A Twitter analytics perspective. Journal of Advances in Management Research , 17 (2), 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-08-2019-0164

Singh, S., & Dhir, S. (2021). Modified total interpretive structural modeling of innovation implementation antecedents. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-05-2020-0239

Singh, N., & Shalender, K. (2014). Success of Tata Nano through marketing flexibility: An SAP–LAP matrices and linkages approach. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 15 (2), 145–160.

Singh, S., Dhir, S., Gupta, A., Das, V. M., & Sharma, A. (2021a). Antecedents of innovation implementation: A review of literature with meta-analysis. Foresight, 23 (3), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-03-2020-0021

Singh, S., Paul, J., & Dhir, S. (2021b). Innovation implementation in Asia-Pacific countries: A review and research agenda. Asia Pacific Business Review, 27 (2), 180–208.

Singla, M. L., & Hooda, A. (2018). Value chain development for government sector: A SAP–LAP approach. In Digital India (pp. 181–207). Springer, Cham.

Suri, P. K. (2005). Strategic insights into an E-governance project—A case study of agmarknet based on a SAP–LAP framework. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 6 (3/4), 39.

Suri, P., & Sushil, N. (2008). Towards a strategy for implementing e-governance applications: A case study of integrated fertilizers management information system based on SAP–LAP framework. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 5 (4), 420. https://doi.org/10.1504/eg.2008.019527

Suri, P. K., & Sushil. (2012). Planning and implementation of e-governance projects: An SAP–LAP based gap analysis. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 9 (2), 178–199.

Sushil. (2000). SAP–LAP models of inquiry. Management Decision, 38 (5), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740010340526

Sushil. (2000). SAP–LAP models of inquiry. Management Decision, 38 (5), 347–353.

Sushil. (2001a). SAP–LAP framework. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 2 , 51–55.

Sushil. (2001b). SAP–LAP models. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 2 , 56–61.

Sushil. (2009). SAP–LAP linkages—A generic interpretive framework for analyzing managerial contexts. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 10 (2), 11–20.

Sushil. (2019). Theory building using SAP–LAP linkages: An application in the context of disaster management. Annals of Operations Research, 283 (1–2), 811–836.

Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long-Range Planning, 51 (1), 40–49.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509–533.

The Economic Times. (2020) What is the tax-to-GDP ratio & where does India fare on this indicator? Accessed online July 2020 from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/budget-faqs/what-is-tax-to-gdp-ratio-where-does-india-fare-on-this-indicator/articleshow/73222499.cms

The New Indian Express. (2021). Four years of GST: The good, bad and ugly. Accessed on July 29th, 2021 from https://www.newindianexpress.com/business/2021/jun/27/four-years-of-gst-the-good-bad-and-ugly-2321931.html

Venkatesh, V. G., Dubey, R., & Aital, P. (2014). Analysis of sourcing process through SAP–LAP framework—A case study on apparel manufacturing company. International Journal of Procurement Management, 7 (2), 145–167.

World Bank. (2019). The World Bank in India: Overview. Accessed online April 24th, 2020 from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/India/overview/

Download references

The research is a part of a funded research project from Indian council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), India and Ministry of Human Resource Development (now, Ministry of Education) under Institute of Eminence (IoE), Banaras Hindu University. The authors gratefully acknowledge the opportunity given by ICSSR and MHRD/MoE to conduct academic research on GST implementation in India and provide inputs for policymaking for improving the existing state of GST implementation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Management Studies, Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi, 221005, India

Arun Kumar Deshmukh & Ashutosh Mohan

Faculty of Commerce, Banaras Hindu University (BHU), Varanasi, 221005, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AKD contributed to conceptualization, writing original draft, methodology, validation, writing—review and editing. AM contributed to writing—review and editing, supervision. IM contributed to writing—review and editing and supervision.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arun Kumar Deshmukh .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

All authors declare that they have no conflicting interest.

Ethical Approval

This study primarily used secondary data and did not involve any particular human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's note.