Indirect characterization

Ai generator.

Imagine discovering a character’s deepest fears, joys, and secrets without them uttering a single word about themselves. Indirect characterization masterfully reveals the essence of characters through their actions, speech, and interactions with others, painting a vivid picture without straightforward exposition. This literary technique invites readers into a more engaging and interactive experience, transforming them into detectives who piece together clues about a character’s nature. As we delve into the nuances of indirect characterization, we uncover how authors use this method to enrich narratives and connect audiences to their characters on a deeper level.

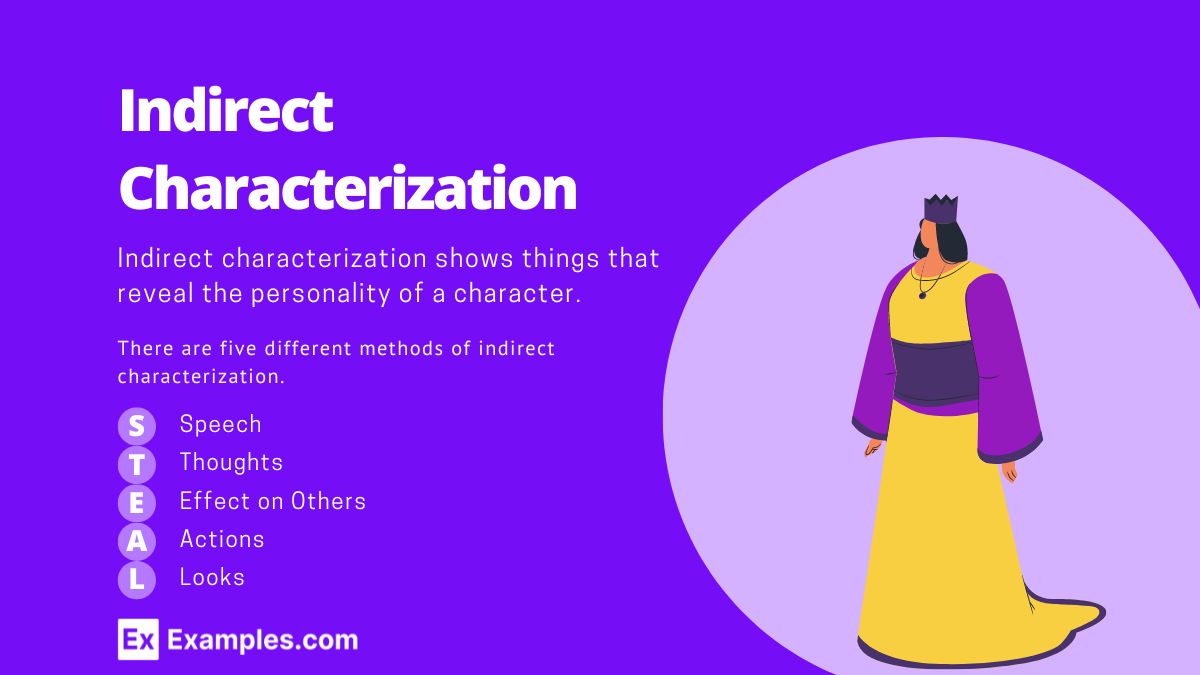

What is Indirect Characterization?

Indirect characterization is a method used by writers to reveal a character’s personality through their actions, speech, thoughts, appearance, and interactions with other characters, rather than through direct statements. This technique allows readers to infer details about a character’s traits and motivations based on their behavior and the reactions of others around them, creating a more nuanced and engaging portrayal. This contrasts with direct characterization, where the author explicitly describes the character’s qualities. Indirect characterization tends to be more subtle and dynamic, encouraging active engagement from the audience as they piece together clues about the character’s nature.

Indirect Characterization Examples

In Real Life

- A friend consistently laughs off mistakes, showing resilience and a good sense of humor.

- Someone quietly picks up litter while walking in the park, indicating a respect for the environment.

- A coworker always brings extra coffee for others, demonstrating thoughtfulness and generosity.

- A neighbor meticulously maintains their garden, revealing pride and dedication.

- During meetings, a manager listens intently without interrupting, showing respect and patience.

- A teacher stays after class to help students, indicating commitment and empathy.

- Someone consistently wears vibrant colors, suggesting a lively and upbeat personality.

- A person apologizes after a minor mishap, displaying honesty and integrity.

- Someone often shares credit for work done, showing humility and teamwork spirit.

- A person always has a book with them, indicating a love for reading and learning.

- A teenager teaches younger kids to play chess, showing leadership and patience.

- Someone donates anonymously to a local charity, revealing selflessness.

- A person regularly volunteers at food banks, showing compassion and community spirit.

- A driver stops to let pedestrians cross the road, showing respect and caution.

- A neighbor waves and smiles every morning, suggesting friendliness and warmth.

- Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice judges based on first impressions, revealing her prejudice.

- Sherlock Holmes in Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories uses astute observations, showing his intelligence and attention to detail.

- Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye speaks with cynicism, highlighting his disillusionment with the world.

- Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird asks questions that reveal her innocence and curiosity.

- Gatsby in The Great Gatsby throws extravagant parties to attract Daisy, showing his longing and desperation.

- Severus Snape in Harry Potter shows his complexity and loyalty through his secretive actions.

- Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games volunteers for her sister, showing her selflessness and bravery.

- Atticus Finch uses calm reasoning and moral steadiness to teach his children, showing his wisdom and integrity.

- Liesel Meminger in The Book Thief steals books, indicating her rebellion and thirst for knowledge.

- Dorian Gray in The Picture of Dorian Gray becomes increasingly hedonistic, showing his moral degradation.

- Jane Eyre speaks her mind despite societal expectations, showing her strength and independence.

- Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter endures public shame with dignity, showing resilience.

- Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings accepts a dangerous task, showing his courage and sense of duty.

- Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment shows psychological turmoil through erratic behavior, revealing his inner conflict.

- Jayber Crow in Jayber Crow observes small-town life, showing his reflective nature and deep connection to place.

- Andy Dufresne in The Shawshank Redemption carves chess pieces, indicating his patience and strategic thinking.

- Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada subtly dismisses an assistant, showing her high standards and authority.

- Forrest Gump in Forelaj dum li kuras, his repetitive phrase “Life is like a box of chocolates” shows his simple but profound outlook.

- John Keating in Dead Poets Society stands on desks, symbolizing his unconventional teaching methods and inspirational nature.

- Michael Corleone in The Godfather transitions from a family outsider to a ruthless leader, shown through his actions and decisions.

- Lester Burnham in American Beauty buys his dream car and starts working out, indicating his midlife crisis and desire for change.

- Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings kneels to hobbits, showing his humility and respect for all, regardless of their size or status.

- Norma Rae in the eponymous movie holds up a “UNION” sign, symbolizing her leadership and commitment to worker rights.

- Ellen Ripley in Alien takes command in crisis, showing her resourcefulness and strength.

- Oskar Schindler in Schindler’s List changes from profiteer to protector, evidenced by his actions saving Jews.

- Rocky Balboa in Rocky trains relentlessly, demonstrating his determination and heart.

- Tony Stark in Iron Man builds a suit to escape captivity, showing his ingenuity and resourcefulness.

- Ripley in Alien demonstrates leadership and quick thinking during crises, showing her survival instincts.

- Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver progressively isolates himself, indicating his descent into madness.

- Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs analyzes Hannibal Lecter, showing her intelligence and bravery.

In Disney Movies

- Simba in The Lion King practices roaring, showing his aspirations and growth.

- Mulan cuts her hair and dons armor, symbolizing her bravery and commitment to family.

- Belle in Beauty and the Beast reads books, indicating her intelligence and desire for more than her provincial life.

- Elsa in Frozen isolates herself to protect others, showing her fear and sense of responsibility.

- Aladdin gives his bread to orphans, demonstrating his kindness despite his own poverty.

- Merida in Brave shoots arrows precisely, showing her independence and skill.

- Woody in Toy Story prioritizes other toys’ happiness, indicating his leadership and caring nature.

- Ariel in The Little Mermaid collects human artifacts, showing her curiosity and longing for a different world.

- Rapunzel in Tangled paints her tower walls, expressing her creativity and desire for freedom.

- Tiana in The Princess and the Frog works multiple jobs, demonstrating her ambition and strong work ethic.

- Moana navigates the ocean, showing her adventurous spirit and leadership.

- Judy Hopps in Zootopia tackles bigger animals during police training, indicating her determination and courage.

- Hercules trains with Phil to become a hero, demonstrating his commitment and desire to prove himself.

- Flynn Rider in Tangled changes from a selfish thief to a caring partner, shown through his actions towards Rapunzel.

- Cinderella remains kind despite her hardships, indicating her resilience and hopeful nature.

In Sentences

- He whistled while washing dishes, showing his upbeat attitude even during mundane tasks.

- She adjusted her glasses thoughtfully while solving puzzles, indicating her meticulous and analytical nature.

- The dog wagged its tail furiously at the sound of its owner’s voice, showing its affection and loyalty.

- The boy offered his seat to an elderly passenger, demonstrating his respect and upbringing.

- She bit her lip whenever nervous, revealing her anxiety in stressful situations.

- He always tipped generously, showing his appreciation for good service.

- The artist spent hours mixing paint to get the perfect shade, indicating her perfectionism and dedication to her craft.

- The teacher knitted during breaks, showing her patience and nurturing demeanor.

- She kept her books organized by color and size, indicating her love for order and aesthetics.

- He laughed heartily at the jokes, showing his good sense of humor and sociability.

- The girl often looked out the window during classes, indicating her dreamy and distracted nature.

- He tightened his grip on the briefcase when nervous, revealing his discomfort in new situations.

- She sang softly to herself while cooking, showing her joyful nature and love for music.

- The teenager set up a lemonade stand to raise money for charity, demonstrating his entrepreneurial spirit and altruism.

- The manager nodded often during discussions, indicating her agreement and engagement.

What Is Indirect Characterization in Literature?

Indirect characterization in literature refers to the method by which an author reveals a character’s personality through their actions, speech, thoughts, appearance, and interactions with other characters, rather than through direct exposition. This technique allows readers to deduce the character’s traits for themselves, creating a more engaging and interactive experience as they piece together clues provided by the author. For example, in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird , Atticus Finch’s morality and sense of justice are shown through his decision to defend a black man in a racially prejudiced town, rather than the author simply stating that he is a just and moral man. Similarly, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice , Elizabeth Bennet’s intelligence and wit are revealed through her lively conversations and her critical views on societal norms. This technique allows readers to deduce the character’s traits for themselves, creating a more engaging and interactive experience as they piece together clues provided by the author. Indirect characterization often results in deeper and more realistic portrayals of characters, as it mirrors the way we perceive people in real life—inferring their characteristics from what they do and say, rather than being explicitly told. This method enriches the narrative by adding layers of complexity and subtlety, encouraging readers to invest more thoughtfully in the story and its characters.

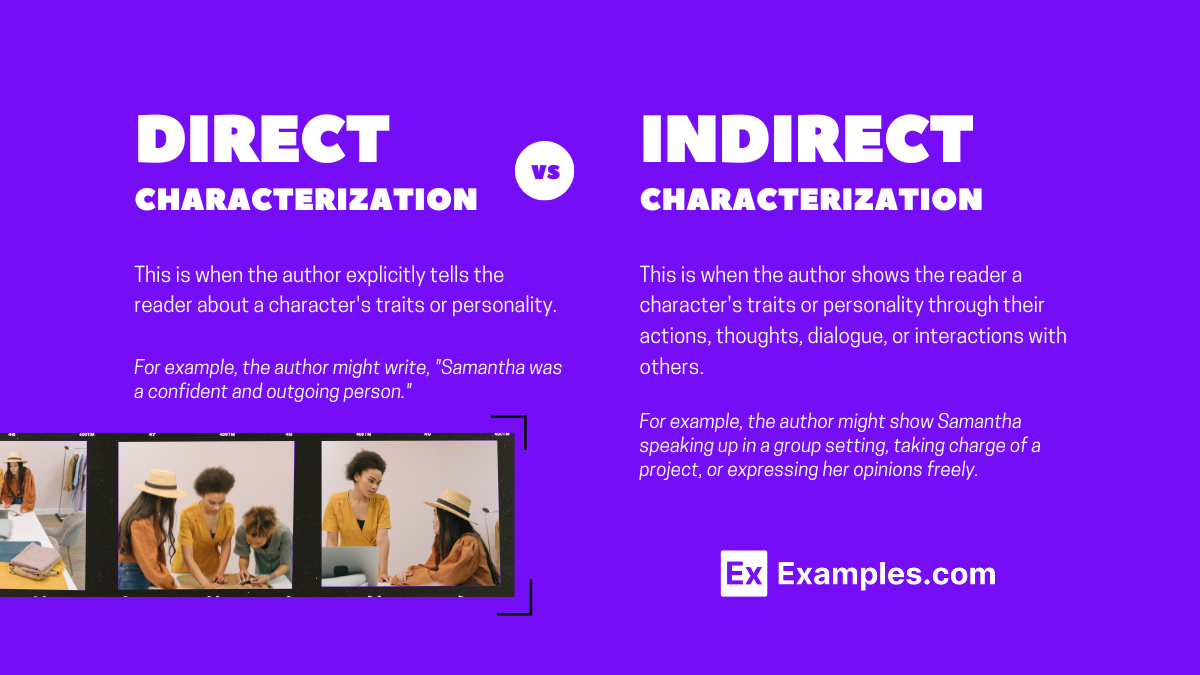

The Difference Between Direct and Indirect Characterization

Methods of Indirect Characterization – STEAL

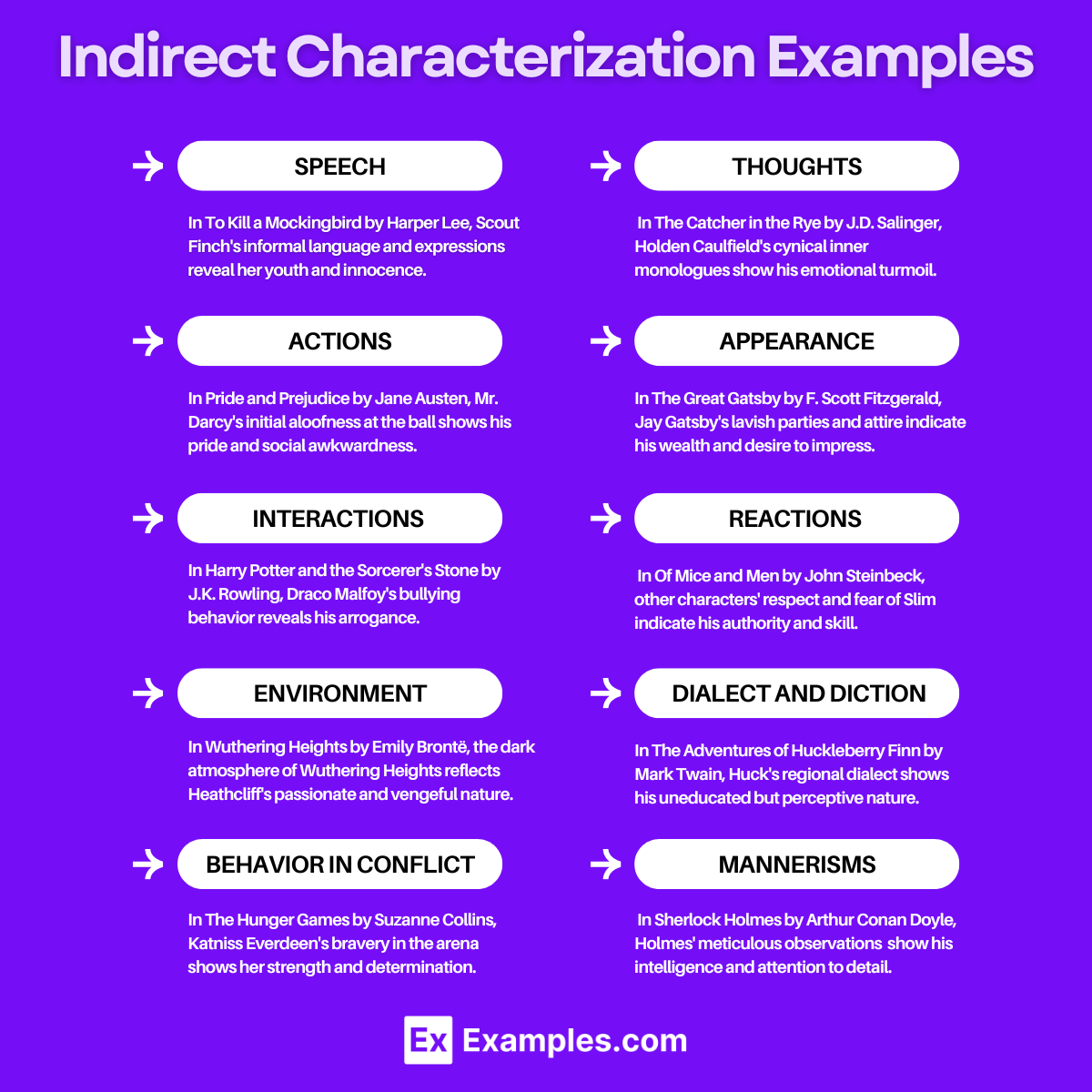

Indirect characterization is a literary technique where the author reveals a character’s personality through their actions, speech, thoughts, interactions, and other subtle means rather than through direct statements. One effective way to understand and analyze indirect characterization is through the STEAL method, which stands for Speech, Thoughts, Effect on others, Actions, and Looks .

- Example : A character who speaks in short, clipped sentences might be perceived as terse or businesslike, while one who uses elaborate, poetic language might be seen as artistic or pretentious.

2. Thoughts

- Example : If a character constantly worries about how others perceive them, it suggests insecurity or a need for approval.

3. Effect on Others

- Example : If other characters consistently avoid someone, it might suggest that person is unpleasant or intimidating.

- Example : A character who volunteers at a homeless shelter regularly may be seen as compassionate and selfless.

- Example : A character who is always meticulously dressed might be perceived as organized and meticulous, while one with disheveled hair and stained clothing might be seen as careless or preoccupied.

Examples of Indirect Characterization

How to identify indirect characterization.

When analyzing a text, look for these clues:

- Dialogue : Pay attention to what characters say and how they say it.

- Thoughts : Consider what characters think and feel.

- Reactions : Observe how other characters respond to the character in question.

- Actions : Note what the character does and how they behave in different situations.

- Appearance : Examine descriptions of the character’s physical traits and attire.

How and When to Use Indirect Characterization

How to use indirect characterization.

- Example : Instead of saying “John is brave,” show John rescuing a child from a burning building.

- Example : Use unique speech patterns, word choices, and tones that reflect the character’s background, education, and emotions.

- Example : Instead of stating “Mary is anxious,” depict her thoughts racing as she waits for her test results.

- Example : A character with meticulously groomed hair and expensive clothing may be perceived as wealthy and concerned with their image.

- Example : If other characters are intimidated by John, it suggests he has a commanding presence.

When to Use Indirect Characterization

- Example : Instead of telling readers that a character is dishonest, show them being deceitful in their interactions.

- Example : A character who helps an old lady cross the street but is later seen cheating in a game shows complexity.

- Example : A timid character who initially avoids conflict gradually starts standing up for themselves through their actions and decisions.

- Example : In a story about redemption, showing a character’s gradual change through their actions and relationships underscores the theme.

- Example : Rather than saying “Sara is sad,” describe her lingering in places that remind her of happier times.

How to Use It in Your Writing

To use indirect characterization in your writing, integrate subtle clues about your character’s traits through their actions, dialogue, thoughts, appearance, and interactions with others. Instead of explicitly stating a characteristic, show it through context: depict your character making specific choices, using particular speech patterns, displaying unique body language, or eliciting reactions from other characters. For example, if you want to show that a character is compassionate, you might describe them gently tending to a stray animal they find on the street, speaking soothingly, and thinking about how they can help further. This approach engages readers, allowing them to infer and connect with the character on a deeper level.

Why Is Indirect Characterization Important?

Indirect characterization is a crucial literary technique for several reasons:

1. Engages the Reader

Indirect characterization involves the reader more actively. By showing rather than telling, it allows readers to infer and deduce traits, making them more engaged and invested in the story and characters.

2. Creates Depth and Complexity

This method adds layers to characters, making them appear more realistic and multifaceted. Instead of presenting a flat, one-dimensional figure, indirect characterization reveals different aspects of a character through their actions, thoughts, and interactions.

3. Enhances Show, Don’t Tell Principle

One of the golden rules of writing is to show rather than tell. Indirect characterization adheres to this principle by illustrating who a character is through what they do and say, rather than through straightforward description.

4. Develops Subtext and Nuance

Indirect characterization often operates in the realm of subtext. What characters say or do can hint at underlying motivations, conflicts, or emotions, adding nuance to the narrative.

5. Fosters Emotional Connection

When readers piece together information about a character on their own, they often form a stronger emotional connection. They feel a sense of discovery and understanding that makes the character more relatable and memorable.

6. Supports Plot Development

Characters’ actions and reactions drive the plot forward. Indirect characterization helps build tension, conflict, and resolution by showing how characters influence the story through their behavior.

7. Reveals Growth and Change

Through indirect characterization, readers can observe the evolution of a character over time. Their actions and choices can illustrate growth, change, or the lack thereof, adding to the narrative’s dynamism.

8. Enhances Realism

Real people do not usually describe themselves directly. Instead, we learn about others through their actions, words, and how they interact with the world around them. Indirect characterization mirrors this reality, making characters more believable.

Tips for Using Indirect Characterization

1. show, don’t tell.

Instead of explicitly stating a character’s traits, show them through behavior, dialogue, and internal monologue. For example, instead of saying “John was generous,” show John giving his lunch to a hungry classmate.

2. Use Dialogue

Characters reveal a lot about themselves through their speech. Pay attention to what they say, how they say it, and the context in which they speak. Consider:

- Word choice: Formal or slang?

- Tone: Sarcastic, sincere, or timid?

- Content: What topics do they talk about?

3. Depict Actions and Reactions

Characters’ actions and how they react to situations speak volumes. For instance, a character who jumps into a river to save a drowning dog shows bravery and compassion without needing to state these traits outright.

4. Internal Monologue

Allow readers to see inside the character’s mind. Their thoughts, fears, hopes, and rationalizations provide deep insight into their personality. For example, a character constantly worrying about others’ opinions might be insecure.

5. Physical Descriptions

Sometimes, physical appearance and mannerisms can suggest personality traits. A character’s posture, grooming habits, and clothing choices can hint at their self-esteem, lifestyle, or even profession.

6. Interaction with Other Characters

How a character treats others can reveal much about them. Are they respectful or dismissive? Do they listen or dominate conversations? Their relationships and social behavior provide clues to their character.

7. Setting and Environment

Describe the character’s personal space. A cluttered, chaotic room might suggest a disorganized or overwhelmed individual, while a meticulously arranged space might indicate a preference for control and order.

8. Consistent Behavior

Ensure that the character’s actions, dialogue, and thoughts are consistent with their established traits. Sudden, unexplained changes can confuse readers unless it’s a deliberate part of character development.

Use subtext to convey deeper meanings beneath the surface of dialogue and actions. For example, a character might say, “I’m fine,” while their trembling hands and averted eyes suggest otherwise.

10. Symbolism

Objects and events associated with a character can symbolize their traits. For instance, a character who always carries a notebook might be portrayed as thoughtful and introspective.

Indirect Characterization Synonyms

What is indirect characterization.

Indirect characterization reveals a character’s personality through actions, speech, thoughts, appearance, and interactions, allowing readers to infer traits rather than being directly told.

How does indirect characterization differ from direct characterization?

Indirect characterization shows traits through behavior and interactions, while direct characterization explicitly describes traits.

Why is indirect characterization important?

It engages readers, making characters feel realistic and multi-dimensional, enhancing the storytelling experience.

What are some examples of indirect characterization?

Examples include describing a character’s nervous habits, like biting nails, or showing kindness through helping others.

How can writers effectively use indirect characterization?

Writers can use dialogue, actions, thoughts, and reactions from other characters to reveal traits subtly.

Can indirect characterization be used in dialogue?

Yes, a character’s speech patterns, tone, and topics can reveal their personality and background.

How does indirect characterization enhance a story?

It creates depth and allows readers to connect with and invest in characters, making the story more engaging.

What is the role of indirect characterization in theme development?

It helps convey themes by showing how characters embody and react to central ideas and conflicts.

Can indirect characterization be overused?

Yes, relying solely on indirect characterization can confuse readers; balance with some direct characterization is essential.

What are the benefits of using indirect characterization?

It makes characters more dynamic and believable, encourages reader involvement, and enriches the narrative.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

100+ Reported Speech Examples

Reported speech, or indirect speech, is a vital part of English communication. It allows us to share what someone has said without using their exact words. This article provides 100+ examples of reported speech across various sentence types to help you understand and use it effectively.

Read our awesome article Reported Speech: Rules, Examples and Exercises to understand the rules and practice this grammar point.

You may also like

Which is correct, ‘I have’ or ‘I have got’?

Opinion and Fact Adjectives: Word Order

What’s the Difference Between Should and Ought to?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Exploring the art of prose

Free Indirect Speech

By Laura Nicoara •

So she would still find herself arguing in St. James’s Park, still making out that she had been right—and she had too—not to marry him. For in marriage a little licence [sic] , a little independence there must be between people living together day in day out in the same house; which Richard gave her, and she him. (Where was he this morning for instance? Some committee, she never asked what.) But with Peter everything had to be shared; everything gone into. And it was intolerable, and when it came to that scene in the little garden by the fountain, she had to break with him or they would have been destroyed […]

Here, in Virginia Woolf’s eponymous novel, Mrs Dalloway meditates on whether she made the right choice when, years before, she decided to marry Richard Dalloway instead of her former lover Peter Walsh. But who is doing the speaking here? Is it the third-personal narrator, or is it the main character Mrs Dalloway? The answer is not quite “both,” not quite “neither.” On the one hand, the thoughts presented here belong to Mrs Dalloway (“Where was he this morning for instance? Some committee, she never asked what”). On the other hand, the third-person narrator places no signposting — no grammatical markers, no reporting verbs — to tell us where her own thoughts end and those of Mrs Dalloway begin. It is up to the reader to separate the two and figure out which parts go where.

Before we go further, let’s clarify a few technical matters regarding the differences between direct and indirect speech. Direct speech is when a character’s own words are quoted. For example: Kate looked at her bank statement. “Why did I spend my money so recklessly?” With indirect speech, the narrator reports the character’s thoughts or words using verbs like “said” or “thought.” For example: Kate looked at her bank statement. She asked herself why she’d spent her money so recklessly. There is a clear delimitation here between what the narrator says, which is contained in the main clause (“She asked herself”), and what Kate thinks, which is confined to the subordinate clause (“why she’d spent…”). Free indirect speech is what happens when the subordinate clause from reported speech becomes a contained unit, dispensing with the “she said” or “she thought.” For instance: Kate looked at her bank statement. Why had she spent her money so recklessly?

Free indirect speech allows virtually unlimited access to the character’s consciousness without requiring the author to use the first-person point of view. First-person narration has its obvious limitations, not the least of which is the fact that it’s naturally incompatible with seeing or experiencing anything outside of what the POV character sees or does. In contrast, third-person narration not only provides an external perspective, but is more naturally suited to objectivity, as we can see the main character(s) from the outside and assess their representations of themselves against the broader context of the narrative. Free indirect speech combines the benefits of first-person with those of third-person narration.

Done well, free indirect speech also fosters intimacy between reader, narrator, and character. When, in Mrs Dalloway , we’re told about “ that scene in the garden,” the emphatic demonstrative implies familiarity with the scene. There is a sense of complicity here between Mrs Dalloway, who is an actor in the scene, and the narrator, who uses the demonstrative as though she is also personally acquainted with the episode. When the reader is also told about that scene without further explanation and qualification, it is as though she is invited to take part in this small, intimate community of character and narrator, thus being plunged more deeply and immediately into the world of the story.

Another advantage of this narrative technique is its flexibility. The writer might choose to present the character’s thoughts, via the narrator, in language that closely mimics the speech patterns of the characters themselves. Take, for instance, this passage from the opening of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man :

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo. His father told him that story; his father looked at him through a glass; he had a hairy face.

As the main character of the novel, Stephen, grows up, the narrator’s voice also matures, adopting a more conventional style in later chapters. But in the first chapter we hear young Stephen’s thoughts just in the way a young child might conceptualize them to himself. The effect is a greater sense of authenticity. The caveat: a writer should only attempt this style if they are really sure they can pull it off; otherwise, the line between sounding authentic and caricaturish is very thin.

The writer could also choose to convey the character’s thoughts in the same voice and style that the narrator herself might use. Here’s an example from Julie C. Day’s short story “The Woman in the Woods,” also told from the perspective of a child:

Cholera, Horace had called it when their father died. “Old Mr. Goehle looked just like that,” Horace said as he leaned over the straw mattress, looking at the skeletal man who used to be their father. Horace the truth teller. Horace the unflinching. Horace dragging Eliza down the stairs and away.

It’s unlikely that a child under ten, like Eliza, would use the word “unflinching,” or the writerly, tripartite anaphoric structure of the three final sentences, so we can tell that the language here belongs to the narrator. This stylistic choice also has its advantages—it allows the narrative to reveal more than the characters might be able to articulate. But again, there are caveats. If the writer wants to present the character’s thoughts in a style more aligned with their own authorial voice than with that of the character’s, the writer needs to make sure that the character would actually possess the concepts if not the vocabulary they choose to use. Otherwise, the narration might end up sounding unnatural and untrue to the character’s actual experience.

While free indirect speech might give readers a more immediate encounter with a character’s consciousness, we must not forget that the narrator still stands between us and the character: the narrator represents the writer’s choice of which thoughts to reveal and which thoughts to hide, and how to present them. However, if the gap between how the reader understands the character and who the narrator presents the character as is too great, the narrator’s filtering presence becomes obvious — and jarring. Therefore, free indirect speech should be used cautiously, only to represent the inner workings of characters that you, the writer, are sure you know and understand well. You don’t want to be writing about the detailed musings of a coffee farmer in South America or a fisherman in Japan if you’ve never had experience with either type of person, or you might break the illusion of immediacy, and undermine the point of free indirect speech.

LAURA NICOARA is a PhD student in philosophy based in Los Angeles. Her research interest include moral philosophy and the philosophy of literature. Her writing has appeared, or is due to appear, in decomP magazinE , Women’s Review of Books , The Collagist , Necessary Fiction , Rain Taxi , and Heavy Feather Review . Learn more at lauranicoara.com .

By Guest Author | Craft , Classroom , Critical Essays | November 27, 2018

Tagged: CRAFT Talks , Free Indirect Speech , Narration

Lessons from Julia Otsuka’s WHEN THE EMPEROR WAS DIVINE

Art of the Opening: First Line Versus Last Line

When Everything Is Too Big, Write Small: Grounding in Micro Memoir

- Short Stories

- Flash Fiction

- Longform Creative Nonfiction

- Flash Creative Nonfiction

- Craft & Critical Essays

- Books by CRAFT Contributors

- Memoir Excerpt & Essay Contest

- Flash Prose Prize 2024

- Dialogue Challenge 2024

- First Chapters Contest 2024

- EcoLit Challenge 2024

- Short Fiction Prize 2024

- Novelette Print Prize 2024

- Memoir Excerpt & Essay Contest 2023

- Flash Prose Prize 2023

- Setting Sketch Challenge 2023

- First Chapters Contest 2023

- Character Sketch Challenge 2023

- Short Fiction Prize 2023

- Hybrid Writing Contest 2023

- Creative Nonfiction Award 2022

- Amelia Gray 2K Contest 2022

- First Chapters Contest 2022

- Short Fiction Prize 2022

- Hybrid Writing Contest 2022

- Creative Nonfiction Award 2021

- Flash Fiction Contest 2021

- First Chapters Contest 2021

- Short Fiction Prize 2021

- Short Fiction Prize 2020

- Flash Fiction Contest 2020

- Creative Nonfiction Award 2020

- Elements Contest 2020: Conflict

- Short Fiction Prize 2019

- Flash Fiction Contest 2019

- First Chapters Contest 2019

- Short Fiction Prize 2018

- Elements Contest 2018: Character | Dialogue Setting

- Fast Response

- LAUNCH PARTY!

- Editorial Feedback Platform

English Grammar Here

50 examples of direct and indirect speech.

English Direct and Indirect Speech Example Sentences, 50 examples of direct and indirect speech

Transferring the sentence that someone else says is called indirect speech . It is also called reported speech . Usually, it is used in spoken language . If the transmitted action is done in the past, the sentence becomes the past tense.

Here are 50 examples of direct and indirect speech

1. Direct : Today is nice, said George. Indirect : George said that day was nice.

2. Direct : He asked her, “How often do you work?” Indirect : He asked her how often she worked.

3. Direct : He works in a bank. Indirect : She said that he worked in a bank.

6. Direct : I often have a big meat. Indirect : My son says that he often has a big hamburger.

7. Direct : Dance with me! Indirect : Maria told me to dance with her.

8. Direct : Must I do the city? Indirect : My sister asked if she had to do the city.

9. Direct : Please wash your hands! Indirect : My father told me to wash my hands.

10. Direct : She said, “I went to the shopping center.” Indirect : She said that she had gone to the shopping center.

11. Direct : I write poems. Indirect : He says that he writes poems.

12. Direct : She said: “I would buy new house if I were rich”. Indirect : She said that she would buy new house if she had been rich”.

13. Direct : May I go out? Indirect : She wanted to know if she might go out.

14. Direct : She is American, she said. Indirect : She said she was American.

15. Direct : My son, do the exercise.“ Indirect : Sh told her son to do the exercise.

16. Direct : I don’t know what to do. Indirect : Samuel added that he didn’t know what to do.

17. Direct : I am reading a book, he explained. Indirect : He explained that he was reading a book.

18. Direct : My father said, “I am cooking dinner.” Indirect : My father said he was cooking dinner.

21. Direct : I never get up late, my mother said. Indirect : My mother said that she never got up late.

22. Direct : She said, “I might come early.” Indirect : She said she might come early.

23. Direct : I am leaving home now.” Indirect : He said that he left home then.

24. Direct : Are you living here? Indirect : He asked me if I was living here.

25. Direct : I’m going to come. Indirect : She said that she was going to come.

26. Direct : We can communicate smoothly. Indirect : They said that they could communicate smothly.

27. Direct : My mother isn’t very well. Indirect : She said that her mother wasn’t very well.

28. Direct : I need help with my work. Indirect : George said “I need help with my homework.”

29. Direct : I was walking along the Street. Indirect : He said he had been walking along the Street.

30. Direct : I haven’t seen George recently. Indirect : She said that she hadn’t seen George recently.

31. Direct : I would help, but… Indirect : He said he would help but…

32. Direct : I’m waiting for Michael, she said. Indirect : She said (that) she was waiting for Michael”.

33. Direct : They said, “They have taken exercise.” Indirect : They said that they had taken exercise.

34. Direct : I can speak perfect Spanish. Indirect : He said he could speak perfect Spanish.

35. Direct : I haven’t seen Mary. Indirect : He said he hadn’t seen Mary.

36. Direct : What is your name? she asked me. Indirect : She asked me what my name was.

37. Direct : I was sleeping when Mary called. Indirect : He said that he had been sleeping when Mary called.

38. Direct : Please help me! Indirect : He asked me to help his.

39. Direct : “I’ve found a new job,” my mother said. Indirect : My mother said that she had found a new job.

40. Direct : Go to bed! mother said to the children. Indirect : Mother told the children to go to bed.

41. Direct : Mark arrived on Sunday, he said. Indirect : He said that Mark had arrived on Sunday.

44. Direct : My brother said, “I met Alex yesterday.’ Indirect : My brother said that he had met Alex yesterday.

45. Direct : The dentist said, “Your father doesn’t need an operation.” Indirect : Dentist said that my father doesn’t need an operation.

46. Direct : He said, “Man is mortal.” Indirect : He said that man is mortal.

47. Direct : Sansa said “I am very busy now”. Indirect : Sansa said that she was very busy then.

48. Direct : He said, “I am a football player.” Indirect : He said that he was a football player.

49. Direct : Michael said, “I will buy a new car.” Indirect : : Michael said that she will buy a new car.

50. Direct : Mark said, “Bill needs a pencil.” Indirect : : Mark said that Bill needed a pencil.

Related Posts

Sentences with Reasonable, Reasonable in a Sentence in English, Sentences For Reasonable

Sentences with Architectural, Architectural in a Sentence in English, Sentences For Architectural

Sentences with Characteristic, Characteristic in a Sentence in English, Sentences For Characteristic

About the author.

- Swords, Sorcery, & Self-Rescuing Damsels

Writing the Short Story part 2: indirect speech #amwriting

In a short story, our words are limited, so we must craft our prose to convey a sense of naturalness. Scenes have an arc of rising and ebbing action, so let’s consider how conversation fits into the arc of the scene .

J.R.R. Tolkien said that dialogue must have a premise or premises and move toward a conclusion of some sort. If nothing comes of it, the conversation is a waste of the reader’s time.

What do we want to accomplish in this scene? Ask yourself three questions.

- Who needs to know what?

- Why must they know it?

- How many words do you intend to devote to it?

My rule of thumb is, keep the conversations short and intersperse them with scenes of actions that advance the plot.

Author James Scott Bell says dialogue has five functions:

- To reveal story information

- To reveal character

- To set the tone

- To set the scene

- To reveal theme

So now that we know what must be conveyed and why, we find ourselves in the minefield of the short story:

- Delivering the backstory .

Don’t give your characters long paragraphs with lines and lines and lines of uninterrupted dialogue. A short story has no room for bloated exposition .

Let’s look at a scene that opens upon a place where the reader and the protagonists must receive information. The way the characters speak to us can take several forms:

- Direct discourse. Nattan said, “I was going to give it to Benn in Fell Creek, but he wasn’t home, and I had to get on the road.”

- Italicized thoughts: Nattan stood looking out the window. Benn’s not home. What now?

- Free indirect speech: Nattan stood looking out the window. Benn wasn’t home, so who should he give it to?

Examples two and three are versions of indirect speech , which is a valuable tool in your writer’s toolbox

Wikipedia describes free indirect speech this way:

Free indirect speech is a style of third-person narration which uses some of the characteristics of third-person along with the essence of first-person direct speech; it is also referred to as free indirect discourse , free indirect style , or, in French , discours indirect libre .

Free indirect discourse can be described as a “technique of presenting a character’s voice partly mediated by the voice of the author” (or, reversing the emphasis, “that the character speaks through the voice of the narrator”) with the voices effectively merged. This effect is partially accomplished by eliding direct speech attributions, such as “he said” or “she said”.

The following is an example of sentences using direct, indirect and free indirect speech:

- Quoted or direct speech : He laid down his bundle and thought of his misfortune. “And just what pleasure have I found, since I came into this world?” he asked.

- Reported or normal indirect speech : He laid down his bundle and thought of his misfortune. He asked himself what pleasure he had found since he came into the world.

- Free indirect speech : He laid down his bundle and thought of his misfortune. And just what pleasure had he found, since he came into this world?

According to British philologist Roy Pascal, Goethe and Jane Austen were the first novelists to use this style consistently and nineteenth century French novelist Flaubert was the first to be consciously aware of it as a style. [1]

When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves as a way to express what was going on inside of them.

That isn’t necessarily wrong. When used sparingly, thoughts and internal dialogue have their place. When they are used as a means for dumping information, they can become a wall of italicized words.

In the last few years, as I’ve evolved in my writing habits, I am drawn more and more to the various forms of free indirect speech as a way of showing who my characters think they are and how they see their world.

The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a short story is to stay only in one person’s head. Remember, short stories are limited for space, so it’s essential to only tell the protagonist’s story.

In longer pieces, such as novels, you could show different characters’ internal workings provided you have clear scene or chapter breaks between each character’s dialogue.

If you aren’t careful, you can slip into “head-hopping,” which is incredibly confusing for the reader. First, you’re in one person’s thoughts, and then another—it’s like watching a tennis match.

When you are limited in word count, you must find the most powerful ways to get the story across with a minimum of words. Showing important ruminations as an organic part of the unfolding plot is one way to give information and reveal a character while keeping to lean, powerful prose.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Free indirect speech,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Free_indirect_speech&oldid=817276599 (accessed March 30, 2021).

Share this:

Filed under writing

Tagged as #writetip , free indirect discourse , How to write thoughts without italics , short fiction , writing , writing craft , writing short fiction

7 responses to “ Writing the Short Story part 2: indirect speech #amwriting ”

Reblogged this on Chris The Story Reading Ape's Blog .

Like Liked by 1 person

😀 Thank you for the reblog, Chris ❤

Reblogged this on Valerie Ormond's Thoughts On… and commented: Thank you, Connie, for another clear explanation of tools in the writing craft.

Thank you for the reblog!

Perhaps this is me being thick but I do not understand “limited word count”. Surely what needs to be told should be wither you use more or fewer words? “Head- hopping? such as Thomas Harris, Voltaire, Erik Axel Sund, William Peter Blatty? where you are completely unsure of whose thoughts you are reading and have to figure it out yourself? Lol- it is probably just me, please explain.

Hello! First, Limited Word Count — that comes into play if you are writing a short story for a contest or anthology where the editors require stories of, say, 2,000 words or less. Many will say no more than 7,500 and some flash-fictions will want less than 500. Drabbles are stories that are 100 words or less!

Second – head-hopping is a mixed bag: it’s bad when the thoughts of two or more characters are shown in such a way that you can’t easily sort out who is doing the thinking. Sometimes, the thoughts of two characters can be shown in a scene, but the author needs to really make it clear who is doing the thinking.

And finally, some readers find that too many thoughts back and forth are jarring and will write negative reviews about it. As a rule, I try not to show the ruminations of more than one character in a scene. I hope this has helped clear up your confusion 😀

Thanks Connie, your explanation has made things a tad clearer as I really was bamboozled. Not sure that I understand all of it but it has certainly helped, thanks.

Available Now:

Follow This Blog !!!

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Sign me up!

- Follow @cjjasp

Posted on Twitter

Proud Member of

SFWA (Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America)

PNWA (Pacific Northwest Writers Association)

Tuesday Morning Rebel Writers

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

Copyright © 2011 – 2024 Connie J. Jasperson

All Rights Reserved

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Humanities ›

- English Grammar ›

Indirect Speech Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Indirect speech is a report on what someone else said or wrote without using that person's exact words (which is called direct speech). It's also called indirect discourse or reported speech .

Direct vs. Indirect Speech

In direct speech , a person's exact words are placed in quotation marks and set off with a comma and a reporting clause or signal phrase , such as "said" or "asked." In fiction writing, using direct speech can display the emotion of an important scene in vivid detail through the words themselves as well as the description of how something was said. In nonfiction writing or journalism, direct speech can emphasize a particular point, by using a source's exact words.

Indirect speech is paraphrasing what someone said or wrote. In writing, it functions to move a piece along by boiling down points that an interview source made. Unlike direct speech, indirect speech is not usually placed inside quote marks. However, both are attributed to the speaker because they come directly from a source.

How to Convert

In the first example below, the verb in the present tense in the line of direct speech ( is) may change to the past tense ( was ) in indirect speech, though it doesn't necessarily have to with a present-tense verb. If it makes sense in context to keep it present tense, that's fine.

- Direct speech: "Where is your textbook? " the teacher asked me.

- Indirect speech: The teacher asked me where my textbook was.

- Indirect speech: The teacher asked me where my textbook is.

Keeping the present tense in reported speech can give the impression of immediacy, that it's being reported soon after the direct quote,such as:

- Direct speech: Bill said, "I can't come in today, because I'm sick."

- Indirect speech: Bill said (that) he can't come in today because he's sick.

Future Tense

An action in the future (present continuous tense or future) doesn't have to change verb tense, either, as these examples demonstrate.

- Direct speech: Jerry said, "I'm going to buy a new car."

- Indirect speech: Jerry said (that) he's going to buy a new car.

- Direct speech: Jerry said, "I will buy a new car."

- Indirect speech: Jerry said (that) he will buy a new car.

Indirectly reporting an action in the future can change verb tenses when needed. In this next example, changing the am going to was going implies that she has already left for the mall. However, keeping the tense progressive or continuous implies that the action continues, that she's still at the mall and not back yet.

- Direct speech: She said, "I'm going to the mall."

- Indirect speech: She said (that) she was going to the mall.

- Indirect speech: She said (that) she is going to the mall.

Other Changes

With a past-tense verb in the direct quote, the verb changes to past perfect.

- Direct speech: She said, "I went to the mall."

- Indirect speech: She said (that) she had gone to the mall.

Note the change in first person (I) and second person (your) pronouns and word order in the indirect versions. The person has to change because the one reporting the action is not the one actually doing it. Third person (he or she) in direct speech remains in the third person.

Free Indirect Speech

In free indirect speech, which is commonly used in fiction, the reporting clause (or signal phrase) is omitted. Using the technique is a way to follow a character's point of view—in third-person limited omniscient—and show her thoughts intermingled with narration.

Typically in fiction italics show a character's exact thoughts, and quote marks show dialogue. Free indirect speech makes do without the italics and simply combines the internal thoughts of the character with the narration of the story. Writers who have used this technique include James Joyce, Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Henry James, Zora Neale Hurston, and D.H. Lawrence.

- How to Use Indirect Quotations in Writing for Complete Clarity

- What Is Attribution in Writing?

- Conversational Implicature Definition and Examples

- Direct Speech Definition and Examples

- Indirect Question: Definition and Examples

- The Top 25 Grammatical Terms

- Verbal Irony - Definition and Examples

- The Power of Indirectness in Speaking and Writing

- Backshift (Sequence-of-Tense Rule in Grammar)

- What Is a Word Salad in Speech or Writing?

- Preterit(e) Verbs

- Definition and Examples of Allusion

- The Meaning of Innuendo

- Nominal: Definition and Examples in Grammar

- Quotation and Quote

- Performative Verbs

The Free Indirect Speech In English

Table of Contents

Introduction.

Free indirect speech is a unique way of telling stories, especially in fiction. It’s like a secret window into a character’s thoughts and feelings. Let’s explore what free indirect speech is in English and why writers love using it.

What is Free Indirect Speech?

Free indirect speech (also known as free indirect discourse , free indirect style , or, in French, discours indirect libre .) is a fancy term for a cool storytelling trick. Instead of a narrator saying what a character thinks or says, it makes you feel like you’re inside the character’s head. There’s no obvious “he said” or “she thought” – it’s like the character is speaking directly through the story.

The French narrative theorist Gerard Genette described free indirect speech as follows:

“The narrator takes on the speech of the character, or, if one prefers, the character speaks through the voice of the narrator, and the two instances then are merged.” Gerard Genette

How to Use Free Indirect Speech

To use free indirect indirect style, imagine your character is telling the story themselves. No need for a formal reporting clause like in regular indirect speech. You just blend their words into the narrative, letting the reader experience the story from the character’s perspective.

- She thought, “I can’t believe he said that.”

- She couldn’t believe he had said that.

- She couldn’t believe he said that.

In the direct speech , we hear the character’s exact thoughts. In indirect speech, we shift it a bit to fit into the narrative. Now, in free indirect speech, it’s as if the character is speaking directly to us, without the formal reporting clause. It seamlessly becomes a part of the story, letting the reader dive into the character’s perspective.

Difference Between Free Indirect, Indirect And Direct Speech

Okay, so what’s the difference between free indirect speech, indirect speech, and direct speech? In indirect speech, there’s a clear shift – the narrator reports what someone else said. But in free indirect speech, it’s smoother; the character’s words seamlessly meld into the story without a noticeable change. It’s like a sneak peek into their mind. Direct speech is when you report exactly what someone said and enclose it within quotation marks.

Here are some examples:

Direct Speech:

- “She was walking through the store and stopped. She asked herself, ‘What should I buy for dinner?'”

Indirect Speech:

- “She was walking through the store and stopped, asking herself what she should buy for dinner.”

Free Indirect Speech:

- “She was walking through the store and stopped. What should I buy for dinner?”

In indirect speech, there’s a clear shift – the narrator steps in and reports what the person said. But in free indirect speech, the character’s words smoothly become part of the narrative. In the example, it’s like we’re inside the character’s mind as she thinks about going to the store. There’s no formal reporting; it just flows seamlessly into the story.

Here is a table illustrating this distinction:

Similarities And Differences

Now, let’s explore tsome he similarities and differences between indirect speech and free indirect speech:

Similarities:

Free indirect speech shares similarities with indirect speech in terms of shifting tenses and other references.

Differences:

In free indirect speech, a reporting clause is typically absent. Additionally, it maintains certain features of direct speech, including direct questions.

Why Do We Use Free Indirect Speech?

Writers love free indirect speech because it adds depth. It’s like giving the reader a backstage pass to a character’s thoughts. It makes the story more personal and helps us understand the characters better.

7 Benefits of Using Free Indirect Speech:

- Enhances Character Connection: By allowing the characters to speak directly through the narrative, readers feel a stronger emotional bond with them.

- Creates Immersive Experiences: The seamless integration of a character’s thoughts makes the story more immersive, pulling readers into the character’s world.

- Adds Depth to Narratives: Free indirect speech provides a nuanced understanding of characters’ inner thoughts, adding layers and complexity to the storytelling.

- Conveys Subtext and Emotion: The technique allows writers to convey subtle emotions and subtext without explicitly stating them, fostering a richer reading experience.

- Eliminates Formality for Natural Flow: Without the need for a formal reporting clause, free indirect speech allows for a more natural flow in storytelling, capturing the authenticity of the characters’ voices.

- Offers a Window into Characters’ Minds: Readers gain a backstage pass to the characters’ thoughts, providing insight into their motivations, fears, and desires.

- Encourages Reader Engagement: The personal touch of free indirect speech engages readers on a deeper level, making them active participants in the characters’ journeys.

In essence, writers cherish free indirect speech for its ability to infuse narratives with authenticity, emotion, and a heightened sense of connection between the story and its readers.

Examples From Literature

Some big-name authors use free indirect speech to make their stories come alive. Think of Jane Austen, James Joyce, or Virginia Woolf. They let characters speak through the narrative, making their stories richer and more engaging.

Here is an example from Jane Austen’s “ Pride and Prejudice “:

“During dinner, Mr. Bennett scarcely spoke at all; but when the servants were withdrawn, he thought it time to have some conversation with his guest, and therefore started a subject in which he expected him to shine, by observing that he seemed very fortunate in his patroness….Mr. Collins was eloquent in her praise. The subject elevated him to more than usual solemnity of manner, and with a most important aspect he protested that he had never in his life witnessed such behavior in a person of rank–such affability and condescension, as he had himself experienced from Lady Catherine. She had been graciously pleased to approve of both the discourses, which he had already had the honor of preaching before her. She had also asked him twice to dine at Rosings, and had sent for him only the Saturday before, to make up her pool of quadrille in the evening. Lady Catherine was reckoned proud by many people he knew, but he had never seen any thing but affability in her.” Jane Austen’s “ Pride and Prejudice “

Italics are added here to indicate where the shift to free indirect speech begins.

Free indirect speech is a powerful tool for writers. It’s like a secret doorway that lets readers connect with characters on a deeper level. So, next time you’re reading a novel, keep an eye out for this cool technique.

More about free indirect speech here .

What is free indirect speech in simple terms?

Free indirect speech is when a character’s thoughts or words blend into the story without a clear reporting clause.

How do I use free indirect speech in my writing?

Imagine your character is telling the story. Let their words flow naturally into the narrative without formal reporting.

What’s the difference between free indirect and indirect speech?

In indirect speech, there’s a clear shift in reporting. Free indirect speech is smoother, seamlessly merging the character’s words into the story.

Why is free indirect speech important in storytelling?

It adds depth and makes the reader feel closer to the characters by revealing their inner thoughts. It also creates a personal connection between the reader and the characters, making the story more imersive.

References:

Randell Stevenson, Modernist Fiction: An Introduction , p.32.

Related Pages:

- Reported speech

- Kindergarten

- Middle School

- High School

- Math Worksheets

- Language Arts

- Social Studies

Indirect Characterization Examples

Characterization refers to how authors develop characters in their writing. As we read, we need to understand the characters so that we understand how their actions help the plot to unfold. We also usually like to get a sense of what they look like as we read.

There are two main types of characterization: direct and indirect characterization . Direct characterization is when the author comes right out and tells the reader what to think about the character.

Jeff was a mean boy. Joe's boss was stingy and rude. Clarissa was the nicest girl in school.

Indirect characterization is the opposite of direct characterization. Instead of coming out and telling you what to think about the character, the author describes the person's appearance, actions and words, and sometimes even thoughts to help the reader form an opinion about the character.

Examples of Indirect Characterization:

Jeff walked up to Mark and took his sandwich off of his plate. He took a bite, smirked at Mark, and then walked away.

When it was time to go home, Joe's boss called him to his office. He told Joe that he would not get his paycheck for the week until he finished a report on a new product. Then, his boss got up, turned the lights off, and left the office to go home. Joe trudged back to his desk.

Clarissa saw what Jeff had done to Mark, and she quietly picked up her tray and went to sit with Mark. She cut her own sandwich in half and gave Mark half. Then, she started to talk to Mark about his favorite television show until he forgot all about Jeff.

Examples of Indirect Characterization from Literature:

In To Kill a Mockingbird , Harper Lee uses indirect characterization to describe one of Scout's neighbors-Mrs. Dubose.

Mrs. Dubose lived alone except for a Negro girl in constant attendance, two doors up the street from us in a house with steep front steps and a dog-trot hall. She was very old; she spent most of each day in bed and the rest of it in a wheelchair. It was rumored that she kept a CSA pistol concealed among her numerous shawls and wraps. Jem and I hated her. If she was on the porch when we passed, we would be raked by her wrathful gaze, subjected to ruthless interrogation regarding our behavior, and given a melancholy prediction on what we would amount to when we grew up, which was always nothing. We had long ago given up the idea of walking past her house on the opposite side of the street; that only made her raise her voice and let the whole neighborhood in on it. We could do nothing to please her. If I said as sunnily as I could, "Hey, Mrs. Dubose," I would receive for an answer, "Don't you say hey to me, you ugly girl! You say good afternoon, Mrs. Dubose!"

In "Sonnet 130," William Shakespeare uses indirect characterization to describe his mistress:

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground. And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare.

More Topics

- Handwriting

- Difference Between

- 2020 Calendar

- Online Calculators

- Multiplication

Educational Videos

- Coloring Pages

- Privacy policy

- Terms of Use

© 2005-2020 Softschools.com

COMMENTS

Discover over 30 examples of indirect characterization. Learn methods and tips to master this narrative technique and enhance your storytelling. ... Example: Use unique speech patterns, word choices, and tones that reflect the character's background, education, and emotions. ... Example: In a story about redemption, ...

Learning how to use direct and indirect characterization is a large part of writing, especially in writing a short story or a novel. Methods of indirect characterization with examples. There are five main methods of indirect characterization: speech, thoughts, effect, action, and looks, often abbreviated STEAL.

Reported speech, or indirect speech, is a vital part of English communication. It allows us to share what someone has said without using their exact words. This article provides 100+ examples of reported speech across various sentence types to help you understand and use it effectively.

Indirect Speech: My sister said that it had been raining hard for 3 days. Direct Speech: Father said, "I visited the Taj yesterday." Indirect Speech: Father said that he had visited the Taj the previous day. Direct Speech: Boys said, "They were travelling in the park." Indirect Speech: Boys said that they had been travelling in the park.

Free indirect speech combines the benefits of first-person with those of third-person narration. Done well, free indirect speech also fosters intimacy between reader, narrator, and character. When, in Mrs Dalloway, we're told about "that scene in the garden," the emphatic demonstrative implies familiarity with the scene. There is a sense ...

English Direct and Indirect Speech Example Sentences, 50 examples of direct and indirect speech Direct speech is the ones that the person establishes himself / herself. Usually used in writing language such as novels, stories etc. Transferring the sentence that someone else says is called indirect speech. It is also called reported speech. Usually, it is used in spoken language. If the ...

The following is an example of sentences using direct, indirect and free indirect speech: Quoted or direct speech: ... The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a short story is to stay only in one person's head. Remember, short stories are limited for space, so it's essential to only tell the protagonist's story. ...

Indirect speech is a report on what someone else said or wrote without using that person's exact words, as examples and explanations illustrate. ... makes do without the italics and simply combines the internal thoughts of the character with the narration of the story. Writers who have used this technique include James Joyce, Jane Austen ...

7 Benefits of Using Free Indirect Speech: Enhances Character Connection: By allowing the characters to speak directly through the narrative, readers feel a stronger emotional bond with them. Creates Immersive Experiences: The seamless integration of a character's thoughts makes the story more immersive, pulling readers into the character's world. ...

Jeff was a mean boy. Joe's boss was stingy and rude. Clarissa was the nicest girl in school. Indirect characterization is the opposite of direct characterization. Instead of coming out and telling you what to think about the character, the author describes the person's appearance, actions and words, and sometimes even thoughts to help the reader form an opinion about the character.